Diaghilev Gets His Due: The Golden Age of the Ballets Russes at the Victoria & Albert Museum

Coilhouse is delighted to welcome writer and dancer Sarah Hassan into the Coilhouse family. Her premiere piece for us is a 3000 word feature about Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes. This is definitely one of the most informative, inspiring, infectious posts you’ll read here this month, so settle in, and enjoy! ~Mer

Dancers in the original Le sacre du printemps production.

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris seems an unlikely venue for a riot. Yet almost one hundred years ago, on May 29th, 1913, fist-fights broke out in an audience made up of socialites, musicians, and artists. The institution in question was one that by today’s standards seems chaste and predictable: the ballet.

The premiere of Le sacre du printemps by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes has become the stuff of legend. Against Nicholas Roerich’s backdrop of a primitive Russia, the radical score by Igor Stravinsky came alive to the choreography of Vaslav Nijinsky, the danseur noble darling – and object of Diaghilev’s affection – whose unsurpassed defiance of gravity on Europe’s great stages had been leaving balletomane’s breathless. Now, the dancer whose roles included a lovesick puppet, a sprightly rose, and a predatory golden slave presented a complicated tableau of sacred ritual. With balled-up fists and downward glances, his dancers jumped and stomped their pigeon-toed feet in time with the violins as if trying to conjure up the ghosts of pagan tribesmen. The heavy woolen dresses painted with folk patterns on the peasant girls were in place of the frothy tulle skirts of nighttime sylphs and bejeweled torsos of slinking odalisques expected from a program a’la Russes.

Nicholas Roerich’s Costumes for Le Sacre Du Printemps.

The production, presenting a ‘new type of savagery,’ caused a literal aesthetic outrage among the haute Parisian audience. Backstage, as the birth of modern dance unfolded, Nijinsky screamed the tempo counts in Russian to dancers who couldn’t hear over the booing, while Stravinsky held him by his coattails lest the crazed choreographer topple into the orchestra. Diaghilev attempted to placate the uproar by turning the house lights on and off. Yet despite its unsuccessful reception, Le sacre du printemps was performed six times, and Diaghilev declared the opening night scandal to be ‘exactly what he wanted.’ It was clear that the ballet was no longer safe.

Thirty-two years after Le sacre’s premiere, Nijinsky, having succumbed to insanity, leapt for a photographer’s camera in a Swiss asylum. The image captured the aging dancer smartly dressed in a suit suspended in the air, proof of his once otherworldly powers. Yet, one can only wonder if the height Nijinsky was attempting to recapture was not his own, but that of the sacrificial virgin he created, dying from her own mad dance in a flash of beastly glory.

The banner at the Victoria & Albert Museum for Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes.

All the hoopla generated by Darren Aronofsky’s psycho-sexual melodrama Black Swan made it easy to believe that ballet had been once again recovered from the ashes of its own antiquity. With Jennifer Homan’s attempt to condense 400 years of history with her book, Apollo’s Angels, the ballet’s ability to survive in an age where anything goes and everything changes came into question – the blood-stained tutu of Natalie Portman’s Nina Sawyer notwithstanding. Madness is, by Aronofsky’s account, the cost of greatness. This idea is artistic old-hat, retold through ballet by Moira Shearer’s exceptional Victoria Page in The Red Shoes – a movie loosely based on Diaghilev and his company – and all the gory details of Swan, from broken toes, bone-thin frames, and endless retching struck a resonant, less glamorous chord. The curtain was pulled back to reveal an art that demands perfection as you claw your way to the top while clawing yourself apart. Ballet, according to Black Swan, is more an arena for the cruel and calculated and less the foundation for beauty, innovation and fantasy.

Oh, how the days of Diaghilev would beg to differ.

It had taken over a century and nothing short of a collection’s obsession for Diaghilev, the mighty impresario, to finally get his due. The week before the opening of Black Swan, I found myself in London to view Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, the exceptionally expansive exhibit which recently closed in January at the Victoria & Albert Museum. It was the making of a balletomane’s dreams; beginning with Imperial Russia and the state of dance in a pre-Diaghilev Paris, the exhibit seamlessly chronicled the Russes from inception to its influences on 1970’s Yves Saint Laurent couture and the modern choreography of the late Pina Bausch. Everything, from costumes, backdrops, photographs, and even Diaghilev’s passports and business ledgers accounting for wigs and shoe dye, were on display. It presented a staggering account of what went into the day-to-day life of the Russes, the artistry it inspired, and the far-reaching legacy it left.

In 1905, outrage had erupted in St. Petersburg over the war with Japan, and the call for the Tsar to end the tyranny of ‘capital over labor’ trickled down from outlying factories to the Maryinsky Theater. Rimsky-Korsakov was dismissed as director of the Conservatory of Music and the strike at the Imperial Ballet – minor in regards to the whole of the Revolution – saw the involvement of no less than three future Ballets Russes stars: ballerinas Anna Pavlova and Tamara Karsavina and Michel Fokine, the company’s first choreographer.

Sergei Diaghilev in his trademark top hat.

At this time, Sergei Diaghilev, a self-taught art historian and opera-lover from Selischi, had been running the influential journal Mir iskusstva (World of Art) with a cultural circle that included Alexandre Benois and Leon Bakst. Having met the tsar on numerous occasions and even holding a brief position at the Imperial Theater, Diaghilev was concerned with the limited artistic opportunities that political instability undoubtedly caused. He took advantage of Russia’s reliance on French loans and sets his sights on the West. In 1906, Diaghilev secured his unofficial position of cultural ambassador with the critical reception of his Paris exhibition on Russian art spanning the last two centuries. This led to a series of ‘historic’ Russian concerts and the production of Boris Gudunov – whose opulent coronation costume by Golovin stood encased in glass at the exhibit – both well-received at the Paris Opéra.

Diaghilev recognized the vast potential of Russian art to appeal to Western audiences, and knew that the key to commercial success and appeal would reside in playing to the prejudices of the country being exotic, bloody, and full of wild theatricality. Russia had the unique geographic advantage to be apart of both the east and west, from the ‘most intentional city’ of St. Petersburg and its European canals to the windy steppe encompassing the borderlands of Central Asia.

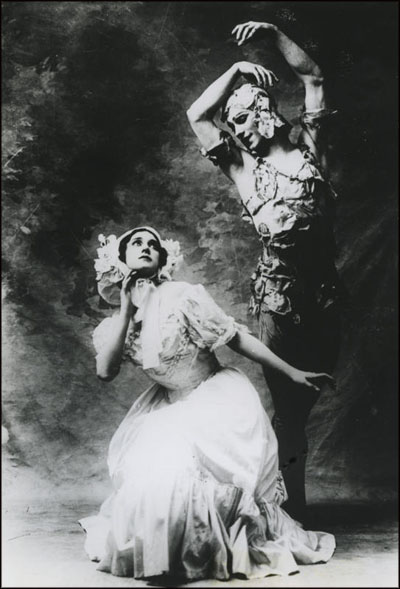

Tamara Karsavina & Vaslav Nijinsky in Le spectre de la rose.

Even after the Tsar had withdrawn all financial support for a joint opera and ballet season abroad, Diaghilev continued rehearsing his new group of dancers trained in the classics and ripe with promise – “repertory can be enlarged,” read the cable to his promoter in Paris, “start big publicity.” Ballet, remarkably cheaper to mount than opera, was about to embark on one of its greatest adventures. Diaghilev took his company of eighty strong to the Paris Opéra where they caused a sensation on opening night in May of 1909, setting a precedent for the next twenty years.

With their high standard of technique birthed from years of training at the Imperial School combined with the refreshing choreography of Fokine, the Ballets Russes ushered in a new era of dance the likes of which the West had never seen. Under Diaghilev’s direction, the Ballets Russes would tackle exoticism, primitivism, Dadaism, Cubism, neoclassicism and eclecticism, as well as push the boundaries for female roles and introduce the male dancer as a soloist rather than a supporting figure. Avant-garde, foreign and mysterious, the cast of characters comprising the Ballets Russes created a legend suiting their leader from the beginning with the charm and virtuosity of Nijinsky to the dark beauty of Karsavina en pointe.

Tamara Karsavina in costume for The Firebird.

Here were dancers that transformed themselves into forest fairies – Les Sylphides – mythical animals – The Fire Bird, Le Coq d’Or – toys, – Petrushka – tribesmen, – The Polovtsian Dances, Le sacre du printemps – gods, – Le Dieu Bleu – and slaves, – Scheherazade – creating innumerable worlds filled with intrigue, danger and romance that inspired fashion, décor and sexuality itself. The audiences of turn-of-the-century Europe devoured the visual delicacies of the Ballets Russes programs with a gusto befitting the company’s continual need for generous benefactors. Such responses ignited the desire for each season to be bigger and bolder than the last.

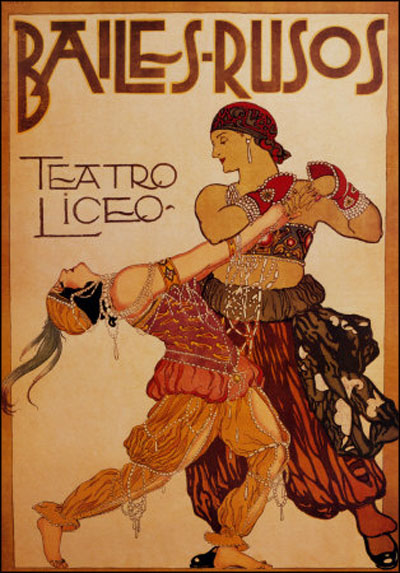

Adolph Bolm & Tamara Karsavina in Thamar.

From his early days in the salons of Paris to creating the Russes, Diaghilev continually proved that his true gifts lay not in the manifestation of his own talent, but in recognizing the talent of others. The creative process was often turbulent, and those who worked to bring each Russes production to life, from Stravinsky and Picasso, to Massine and Larionov, also brought uncanny temperaments to the table.

Posters designed by Jean Cocteau, 1911.

A comprehensive history of the Ballets Russes would include the slamming of doors and explosive arguments over invention, private affairs and public image. After all, any company that intends to make equal players of its collaborators is bound to bruise a few egos along the way. The Ballets Russes was most impressive for its ability to cohesively bring together dance, design, and music, and Diaghilev’s relentless demand of ‘astonish me!’ to the artists he employed kept the company performing at the height of their powers.

Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky in 1921.

Since Diaghilev never allowed performances to be filmed, future generations were to rely on surviving artifacts of the Russes in order to comprehend the overwhelming amount of artistry that went into each ballet. The impressiveness of the exhibit at the Victoria & Albert reminded viewers how much had survived – and, in turn, how much undoubtedly had been lost – which ended up mostly in the museums and private collections of Europe.

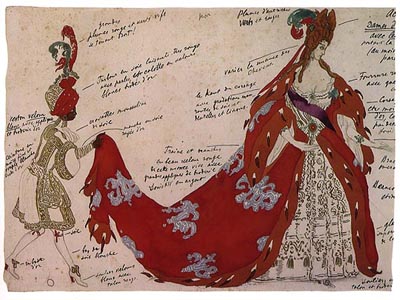

One of the most thrilling aspects of the exhibit was the generous presence of costume. The amount of design that went into a Russes production was no small feat; one only has to look at the notes on Leon Bakst’s sketches for costumes that would never see the light of day compared to those that did.

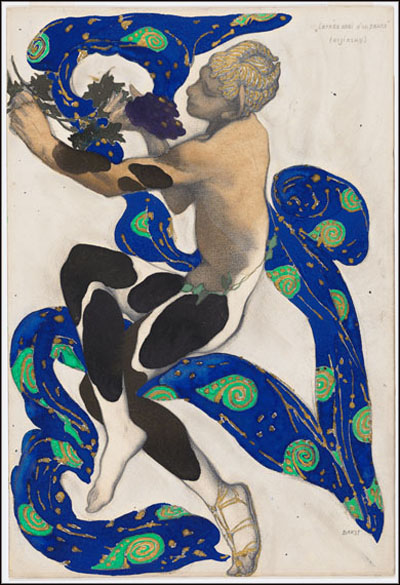

It was Bakst’s designs, along with the couture fashion of French designer Paul Poiret, that inspired the wave of vogue Orientalism in Western Europe. With his costumes for Scheherazade, Cléopâtre, Narcisse, Le Dieu Bleu and Daphnis and Chloë, Bakst incorporated loose silhouettes, exaggerated jewelry, bare feet and shocking color.

Bakst’s costume design for Cléopâtre.

Bakst’s costumes for Daphnis and Chloë.

Mikhail Fokine & Vera Fokina in Scheherazade.

For Scheherazade, famously starring Nijinsky as the Golden Slave, Bakst turned the stage into an ornate oasis of pleasure and imminent terror with his harem backdrop of black, greens and pinks, accessorizing with heavy drapery and hanging lanterns. The saturated eroticism of Nijinsky seducing his Zobeide, dripping in gems and silk, caused frenzy for everything “Eastern,” from baggy Turkish trousers as day wear to Cartier’s setting of sapphires and emeralds together for first time since the Mogul emperors.

Bakst’s talent for capturing the eye with sumptuous color, shape and proportion continued to be seen in the towering headdresses and intricate beading on the costumes for the Hindu-inspired Le Dieu Bleu, as well as the vibrant patterns on the belted tunics for Narcisse and Daphnis and Chloë. The artists of the Ballets Russes were no strangers to the symbolist sentiment towards the ancient cultures of Persia, Siam and Egypt, but their interpretations lent themselves towards delighting the senses rather than rewriting history.

Nicholas Roerich found inspiration in Russia’s own eastern flavorings with his designs for The Polovtsian Dances, pairing blues and reds with jagged prints that would spill into his costumes for Le sacre, and Natalia Goncharova concentrated on a sunset palate for the set designs for Le Coq d‘Or and The Firebird.

Bakst’s backdrop design for Scheherazade.

Natalia Goncharova’s backdrop for The Firebird.

Pablo Picasso’s costume for the Chinese Conjurer in Parade.

Surviving a burial in Poland during the war years, Pablo Picasso’s costume for the Chinese Conjurer in Parade illustrated the geometry and boldness of Cubism – prompting a ‘breath of fresh air’ in a ‘hot house’ of exoticism – found also in his designs for Massine’s Spanish-flavored Le Tricorne. For the Ballets Russes, Diaghilev commissioned the talents of no less than forty artists, some of whom would become major figures during the twentieth century, from said contributors to Jean Cocteau, Henri Matisse, and Coco Chanel.

With all the innovation placed on the visual, the exhibit graciously acknowledged the dancers who made up the working heart and soul of the Russes. Costumes didn’t just display materials; they were brought to life by the dancers, such as the metal wings on Lydia Lopokova’s dress for Les Sylphides to Karsavina’s toe shoes showing faint blood stains underneath the pink satin. But it was Vaslav Nijinsky – long has he reigned as most famous of all male dancers – who required his own display in the museum.

Vaslav Nijinsky as ‘The Golden Slave’ in Scheherazade.

Each role he filled, from the spirit of the rose, to Albrecht in Giselle, Nijinsky had the chameleon-like ability to never appear exactly the same in photographs – perhaps in part to the play of light and shadow on an already illusive figure.

His choreography for the ballets L’aprés-midi d’un faune and Jeux confronted the themes of sexuality head-on, with the mimed masturbation ending faun to the sporty meditations of a threesome in Jeux. Nijinsky’s creations, still danced to this day, premeditated the modernist scandal of Le sacre and affixed the star in line with talents other than his unforgettable dancing.

Bakst’s sketch of Nijinsky as the faun in L’aprés-midi d’un faune.

Yet it was to be his legacy and tragedy off-stage that endured long after the curtain had fallen. As Diaghilev’s younger, tempestuous lover, Nijinsky held the heart of the dominant impresario in his haughty hand until his secret marriage to Romola de Pulszky led to his dismissal from the Russes in 1913.

Later on, Nijinsky divulged the details of Diaghilev and his homosexuality – which left him sick, on and off – in his diaries filled with writings and illustrations birthed from a madness that eventually crippled him. His good looks, captivating stage presence and genius had catapulted the role of the male dancer as a soloist, but it was the record of insanity he left behind that did little to dispel the mystery regarding one of the great artists of all time.

Rehearsal of Les Noces, 1923.

Following the trend of innovation started by Fokine and Nijinsky the choreography and concepts for the Russes’ ballets became more complex and boundary-pushing. Bronislava Nijinska tackled the tradition of a Russian peasant wedding with Les Noces, allowed ballerinas to sashay with sexual sophistication in Les Biches and imagined Parisian vacations a la’ Chanel with Le Train Bleu. Exoticism stood by the wayside as capital disaster loomed over The Sleeping Princess, Diaghilev’s ode to his love of the classics.

Bakst costume notes.

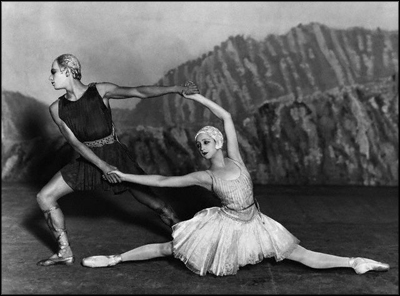

George Balanchine, who would go on to found the New York City Ballet, flexed his minimalist muscles with Apollon musagéte and Prodigal Son, two staples of his surviving company. Chinese influence bled into the opulence of Le Chant du Rossingnol and Ode employed futuristic light shows and outfitted the dancers in white bodysuits. There was little that the Russes seemed ill-equipped to carry out in response to the changing cultural moods of the twenties, and work was omnipresent wherever the company called home.

Alexandra Danilova and Serge Lifar in Apollon musagéte.

Regencies, no matter how glorious, always come to an end, and when Diaghilev died in 1929 while in his beloved Venice, production in the greatest of cultural kingdoms came to an abrupt halt. Tensions mounted, loyalties were tested and the uncomfortable question of how to carry on without the impresario was answered by off-shoot companies that survived as long as the public could stomach the faint tracings of splendor.

Despite the cultural stamp made permanent by the Ballets Russes, ballet slipped through the cracks as a daring institution and came in and out of vogue for the greater part of the past fifty years. Royalty was made out of the brightest in the business, from Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, to Mikhail Baryshnikov, Natalia Markarova, and Suzanne Farrell.

Russian commemorative stamp honoring the Ballets Russes.

But the days when dancers were treated like Hollywood celebrities, from appearances in the gossip columns to spots on The Muppet Show, have all but disappeared. No company has ever been able to recapture the glory of the Ballets Russes and the cult of celebrity it inspired, from its evolution of the ballerina beyond the tutu to its influences on high fashion and decorative arts.

If he were alive today, Diaghilev may have a difficult time understanding what currently inspires performers and the work that is truly passed off as ‘art.’ Yet it is difficult, nay horrific, for me to imagine a world without him and the lasting beauty he birthed, for what is beauty, but ‘the beginning of terror, which we still are just able to endure?’ Audiences, thanks to the Victoria and Albert, were given the rare opportunity to endure the artistry of the Ballets Russes and begin again its cycle of wonder.

Diaghilev and his dancers, Liverpool, 1928.

April 11th, 2011 at 6:45 am

Wonderful post. Thank you.

April 11th, 2011 at 7:37 am

Lovely article, and photographs.

April 11th, 2011 at 4:29 pm

Oh SARAH. Gorgeous piece. You covered like, 90% of my favorite things ever.

Rx,

Dusty

April 11th, 2011 at 5:07 pm

Beautiful, beautiful and so very informative.

April 27th, 2011 at 6:57 am

Lovely post.Thank you.

September 13th, 2011 at 1:09 pm

[…] Diaghilev and Stravinsky found here […]