Indie Indigenous: Virgil Ortiz and the Changing Face of Native Art

Editor’s note: below is the final installment of a three-part series by Rachel “Io” Waters about contemporary native art and culture. The first two blog posts in this series, and the intro post, can be found here, here and here.

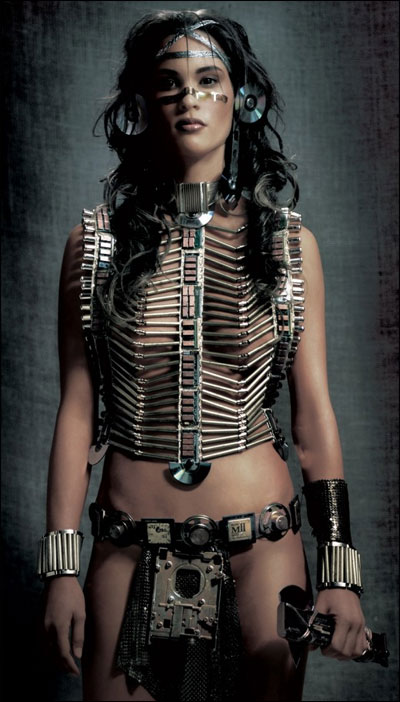

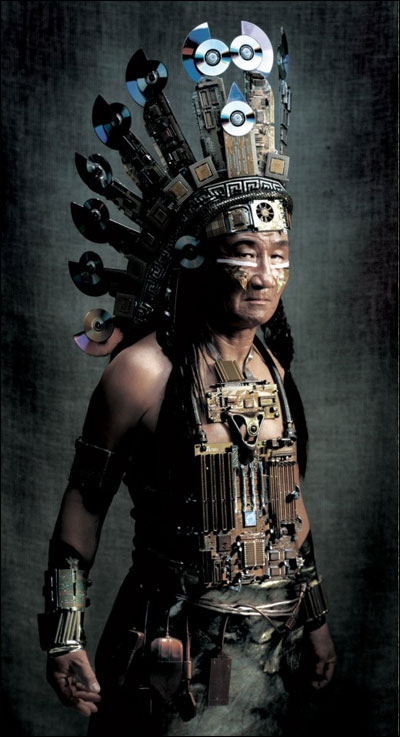

Image from Virgil Ortiz’ Venutian Soldiers series

There is this notion of Native American art that permeates the collective psyche. Often the mental images evoked are those of pastel landscapes with painted horses galloping along sandstone cliffs or of noble maidens snuggling with wolves, created by artists whose only contact with native culure appears to come from Harlequin covers. It’s the type of art best reserved for the walls of Best Western hotels and 24 karat gold-rimmed collector’s plates. Pleasant. Bland.

Enter Virgil Ortiz, a painter, fashion designer, stylist and ceramicist from Cochiti Pueblo whose work challenges every notion of how native art should look. At once traditional and futuristic, whimsical and post-apocalyptic, Ortiz’s art transcends classification altogether.

From 2010’s Contortionista series which melds 19th Century Pueblo Munos figures with the sensual lines of modern Cirque performers.

With a reach extending far beyond the borders of his home state of New Mexico, Ortiz has created prints for fashion giant Donna Karan and continues to expand his own fashion line into the realms of clothing and accessories.

In August of this year, Ortiz premiered his latest project “Venutian Soldiers” during Indian Market in Santa Fe, NM. Inspired by “America’s First Revolution,” the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Ortiz showcased a series of ceramic work and photography depicting an army of futuristic, indigenous superheroes outfitted with feathered gasmasks and latex loincloths.

Image from Virgil Ortiz’ Venutian Soldiers series