A Telling of the Tale of Tales

The PATH —– Launch Trailer from Tale of Tales on Vimeo.

Belgian avant-garde Game Developers Tale of Tales have made a name for themselves as an independent game development studio, creating genre defying art-games. Armed with ambitious vision and an unrelenting sense of artistic integrity, Tale of Tales co-founders Michaël Samyn and Auriea Harvey cater to an audience outside of mainstream gamers providing complex, meaningful gameplay experiences, and offering a “different kind of story” for “a different kind of people”.

One of their first offerings, The Endless Forest, is a multi-player game set in a soothing, bucolic landscape; there are no goals to achieve, or rules to follow – “just run through the forest and see what happens.”

The Graveyard, launched in 2008, is a short tale which places the player in control of an old woman traversing a straight and narrow path across a gloomy graveyard. It is described as “an icon” of the studio’s work as a result of the game’s “apparent simplicity and vagueness”.

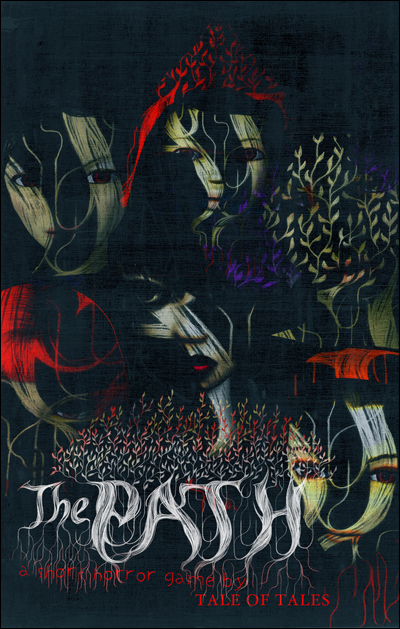

Tale of Tales next endeavor, The Path, is loosely categorized as “adventure-horror” and was inspired from the classic fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood. There is one rule in the game, which needs to be broken. There is but one goal. And when you attain it, you die. It is “a game about playing, and failing, about embracing life, perhaps by accepting death.” The legendary SWANS member Jarboe, along with multitalented co-composer Kris Force, provide an dynamic, unsettling narrative and score.

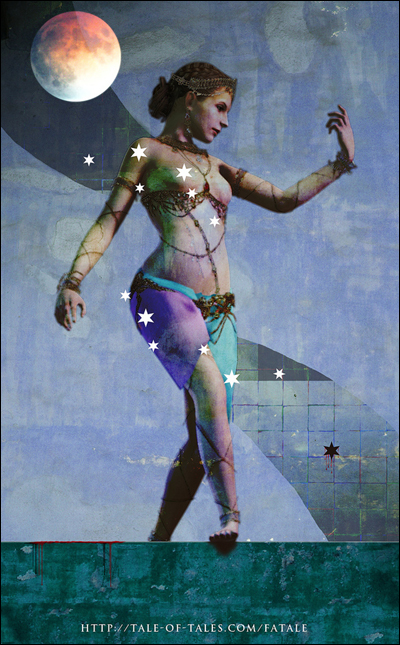

Based on Oscar Wilde’s Salome, a play banished from the stages for over 50 years, Fatale is the studio’s latest gaming project. An interactive 3D vignette, it offers the same sort of “observational immersionist” approach that Tale of Tales has become known for. The player is encouraged to “explore a living tableau filled with references to the legendary tale and enjoy the moonlit serenity of a fatal night in the orient.”

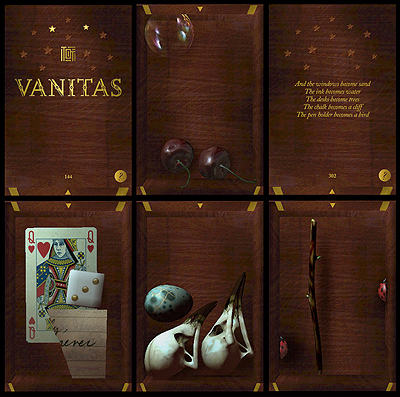

2010 saw the release by Tale of Tales of Vanitas, an app for iPhone and iPod touch. Referencing the still life paintings from the 16th and 17th century, Vanitas presents one with a 3D box filled with “intriguing objects…to create pleasant arrangements that inspire and enchant”, and is touted as a “a memento mori for your digital hands.” The app includes random quotations on the topic of life and vanity and music by avant cellist Zoë Keating.

Michael and Auriea graciously gave of their time to provide a thought-provoking look into the passionate philosophies behind Tale of Tale’s creative projects. See below the cut for the full interview.

COILHOUSE: Can you tell our readers a little bit of how Tell of Tales came to be? A “once upon a time”, as it were?

TALE OF TALES: Tale of Tales is the name of our company. But we’re essentially a couple, a married couple even. So our “once upon a time” is a love story! Once upon a time, there was an internet without Facebook. An internet without Myspace or Twitter. An Internet, even, without Google. There were no advertisements on websites. And spam did not exist. This digital Garden of Eden place was inhabited solely by smart, creative and beautiful people. Everybody was making things for everybody else. We all learned together. A small group of us gathered in Hell (hell.com, to be precise) to see if we could get a taste of some forbidden fruits together.

One -dark and stormy- night, we met in a videochat application. A rare thing in those days, when most people still connected through modems. We wanted to see if we could use the technology for artistic purposes. Among the guests were Auriea Harvey, well known for her stunning lush artwork at entropy8.com, connecting live from New York City, and Michael Samyn, the odd inventor of zuper.com, from his huge and windy loft in an abandoned factory in Belgium. Auriea was broadcasting blurry black and white web cam streams of herself and Michael, cameraless, showed pictures of flowers and vegetables. The two quickly found a private chatroom and connected on a level that far surpassed anything that the technology was supposed to allow for.

The next day we started collaborating. And we haven’t stopped since. That was in the sacred year of 1999, when the future still existed. The first thing we made together was Skinonskinonskin, a string of love letters in Dynamic HTML, created because we felt that interactive pieces more adequately expressed how we felt in those days. We also made plans to work together professionally, from the very start. We merged our domain names into one -entropy8zuper.org- and created our first website, Genesis, together, remotely. By some strange coincidence -although we had little belief in such things in those days- we both ended up in San Francisco at the same time. So we launched our website from a tiny laptop in our hotel room, where we met for the first time, in the flesh. Despite our most sincere efforts, we were chased out of the Garden and Auriea moved to Belgium.

A few years and hundreds of websites later, we turned our attention to videogames as an artistic medium, which is when we started Tale of Tales. And we’re still trying to slay that dragon.

I read something you said in a previous interview, which really struck a chord within me. You note that Marcel Duchamp once defined art as some kind of electricity that happens between the work of art and the viewer – and that “the artist himself is absent in this definition.” You go on to say that you believe that “interactive media has the potential to produce the greatest art ever precisely because of this central role of the observer.” Can you tell us about the process of creating a game where so much is left to the interpretation of the viewer/player? I know you’ve gotten a great deal of positive response, award nominations etc. (The Path, I’ve read, was “one of the most successful independent games ever designed”) – was a this surprise, considering this unconventional type of gameplay?

We think this goes further than interpretation. Or not as far, if you look at it as an author.

In all of art history, and culminating in the glorious 19th century when all this history came together -before it was utterly eroded by modernism- there is a desire of the artist to immerse the viewer in their artwork. They want to embrace their reader through their poems, envelope them in their landscapes, touch them through their sculpture and so on. And a lot of members of the audience feel the same. This is what Duchamp noticed. And he identified this connection between the artwork and the viewer as the artistic experience.

The fact that the author is not present when this happens, does not mean that the author does not desire this to happen. The idea that art is some kind of narcissistic exercise concerned solely with the expression of the emotions or ideas of its creator is fairly alien to the actual artistic practice. We think of artists as mediums, as messengers. They receive messages from “elsewhere” or observe things that other people might not see, and they forward these messages or point out these things to their fellow men. As Duchamp has also noted, artists are often not completely aware of what their artwork really means. They work on instinct and create “what feels right.”

The non-linear, interactive medium allows the artists to actively include this indetermination, this potential infinity of meaning in the creation process. That’s what makes this medium so revolutionary. And why we think it offers the artistic solution to the post-modern impasse. As a game designer, you don’t need, you don’t even want to offer the player a single picture, a single message. We think of our own creations as tools. Tools for exploring certain themes. We do this as creators, during the development. And the audience continues this exploration when interacting with the system.

The positive response from the games community, and especially the games press, did indeed come as a surprise. Even though we took great care in making The Path as accessible as possible, we were well aware of the fact that our choice in subject matter and our “gentle” style of interaction design might not appeal to the games audience. We in fact didn’t make The Path with this audience in mind. We wanted to reach people who do not play videogames more than anything. We had expected nothing but a lukewarm reception from the gamers.

While the games audience may not be the most appreciative, or knowledgeable or experienced, in terms of art, there is a strong desire for “more”. Everyone who has enjoyed this medium can feel its power, its potential. But very few development studios or publishers are willing to explore this potential. The games industry is very successful and they don’t see the need for taking what they consider to be unnecessary risks. This is probably part of the reason why our work was so well received. Maybe the reviewers didn’t exactly like or understand The Path, but they passionately appreciated the fact that we were experimenting with the medium, that we are trying to pull it, kicking and screaming, towards the realization of its potential.

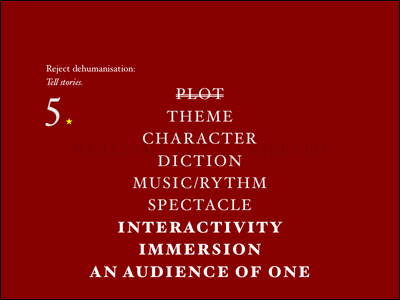

In a “Ten reasons why computer games are not games” blog posting from 2007, you have a punch list of “Not to be forgotten aspects of videogame design”; items that one would assume probably are most likely overlooked in current videogame releases. To name a few, you’ve listed – “atmosphere”, “flow“,“art“,“direction“,“narrative world concept“, etc. These are all things that are apparent you take quite seriously to anyone who has played any of your releases … can you tell us why these things in particular important to your vision? And having done this for a few years now – has this list changed? Is anything on it any more or less important to you? Anything to add? Are you starting to see more evidence of these things in videogame releases as we move forward?

None of these things are more important than any of the others. That was sort of the point of that article. That for us, the creation of videogames is about combining all these different elements so that they support each other and all contribute to the experience. We felt we needed to point this out because in general, the games community tends to focus almost exclusively on game design as the one factor that is most important. To the point where the spectacular (and expensive) graphics are often downplayed as mere eye candy. This is in fact very ironic, considering that game design hasn’t really evolved much since the days of Pac Man and Space Invaders.

We see a lot of commercial development studios spend a lot of effort and time and money on the creation of elaborate virtual worlds, only to shut them off from exploration by making all sorts of game playing demands from the audience. While most of the effort of creation is put in simulation, aesthetics, atmosphere, and so on, they still feel that the few weeks they spend on the actual game design are more important than anything else. We think that is a pity. And extremely negligent. Not only in artistic terms but also in commercial ones. We believe that there is a huge audience out there for immersive interactive experiences. The audience that now watches films and reads books -so, practically everyone. And the game industry actively rejects this opportunity because of some misplaced loyalty to an outdated idea that the game design is the most important element in a videogame and should be above everything else.

As videogame worlds get more sophisticated and videogame narratives more appealing, it’s almost unavoidable that this barrier will be broken at some point. That videogames will be made accessible for those who are not so interested in competitive interaction, or who simply prefer to keep their sportive activities and their art appreciation separate. At that point, we will all be astounded about how foolish the industry has been, for such a long time. And how selfish, in a way.

That being said, there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done to make this new medium as appealing as the old to as wide a variety of people. The shift from linear media to real-time media is quite radical. And a lot of research and development will be needed to realize the potential of the new. We like to think that our work contributes to this exploration.

In your games, you’ve created “circumstances which for viewers can create their own experiences”; some examples of which can be found in The Path, an eerie game whose narrative is based on the tale of Little Red Riding Hood, and The Graveyard, in which one plays an old woman visiting a cemetery. More recently there is Fatale, an “interactive vignette” inspired by the story of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. These circumstances you’ve built the games around… while certainly varied, seem to have an underlying basis in old stories, folk tales fraught with lurking perils – the loss of innocence or the spectre of death, etc – these are uncanny, unsettling themes! What draws you to these stories again and again? What inspires you to build upon them, pull from them? Additionally, I would love to know what it was from about Salomé that intrigued you so…and does Fatale enjoy the same positive response of the earlier two titles?

As an aside, we don’t build games “around circumstances” as you are suggesting. Instead, we try to extract circumstances from stories that we hope allow us, creators and players alike, to explore the themes we find in these stories.

We don’t think the themes we choose are particularly unsettling. On the contrary. They make more sense to us. They help us understand our own lives, our own feelings. We think happy and heroic stories found in most entertainment are not only false, they are also very damaging. They make us believe that a life that doesn’t match up with these heroic quests or these happy romances, is somehow inferior. That the complexity of real life is just a chaotic problem that should find a simple solution. This desire for simple answers and clean truths is detrimental. It’s depressing and destructive.

We are attracted to stories that embrace the complexity and ambiguity of life. That delve deep into the unexpected twists that a human mind is capable of. Because it is moving. And beautiful. And because we recognize it. Our characters don’t strive for simplicity or some way to “win”. They are, in a way, far more heroic than that. They want everything. They are not making any compromises. Love and death. Destruction and peace. Everything at once. We admire them. When we grow up, we want to be Little Red Ridinghood.

Or Salomé. Salomé kills the man she loves because he does not love her. Is there a more beautiful thing in the world? A more romantic one? We have a thing with these femmes fatales. We don’t see them as evil or frightening. They are passionate and determined. Men don’t just fall victim to them. Men give themselves to them. It is the ultimate beauty. To be loved so much. Or to love so much. And since we also had a thing with Middle Eastern aesthetics, we chose Salomé to make a piece about.

Sadly, Fatale is not nearly as well received by the games press as The Path was. Which is kind of disappointing because of its utter predictability. In The Path, we really did our best to make a game that appealed to a wide audience. Since that was well received, we wanted to see what would happen if we just worked on instinct, without caring to much about the players. It was a good test. Lesson learned: if you want a wider audience, you need to work for it. We’re ok with that. Some of our pieces are more suitable for an expanded audience. Others need to remain more special, and appeal only to a small elite.

The Making of The Dance of The Seven Veils from Tale of Tales on Vimeo.

From the eerie score to the exquisite scenery to the delightfully nuanced characters – you obviously work with a brilliant team of people. What can you tell us about the artists and the musicians you work with to put projects like these together? Though I imagine you are quite thrilled with your current assemblage of folks, is there anyone whose art/aesthetic/ you admire who you think shares your philosophy/vision that you would add to a “dream team”?

We always work with people whose work we admire. We never have any vacancies. When we think of a project, we also think of the artists we would like to have involved. Between the two of us, technically, we can handle every aspect of production. But when the budget allows it, we love to collaborate with artists we respect, and who understand what we’re trying to make. We’re not managers. We realized that quickly enough in the beginning of our games development career when we tried to hire people to do certain jobs. That was never a fluent experience. And we lost a lot of time trying to get people to do what we wanted. Time we should have been spending on making our videogame. So now we only work with artists of whom we know they are going to deliver something that is better than what we expected, and without any hand holding. We often think of our games as platforms, or a sort of galleries, where these artists showcase their work.

That being said, we tend to collaborate with the same people repeatedly. Laura Raines Smith, for instance, is more or less the unofficial third member of Tale of Tales. She has animated all main characters in all our games so far. It took a while to find her, but once we did, we never let go. Tale of Tales would not be Tale of Tales without her sensitive and nuanced approach to character animation. Or her insane amounts of energy. And then there’s the composers and sound artists. Local singer songwriter Gerry De Mol has contributed to three games (The Endless Forest, The Graveyard and Fatale). Jarboe to two (The Path and Fatale), as composer and as voice actor. And Kris Force also on three projects (The Graveyard, The Path and Fatale), as sound designer and musician. For Vanitas, Zoë Keating recorded small atmospheric cello phrases. We hope to work with her again in the future. Lina Kusaite has created beautiful concept art for The Endless Forest and 8. And Marian Bantjes made the logo and calligraphy for The Path.

To be able to work with Takayoshi Sato on Fatale, was a dream come true. We had always admired his modeling and character design work in Silent Hill 1 and 2. Another dream in the making is our current collaboration on an iPad game with British designer Alex Mayhew (of Ceremony of Innocence fame, a very influential work for us). And we’re prototyping a project to which we hope and pray code artist Robert Hodgin will be able to contribute some of his elegant algorithms. And finally, we have a secret dream of making one of Ray Caesar’s 3D scenes interactive. We’ve discussed it before. Hopefully it will happen one day.

Is there anything you are developing currently that you can share with us? What are some future Tale of Tale releases that we can look forward to?

We are currently prototyping two new projects, simultaneously, switching between them every month. This way we can stretch development time to twice as long for both projects. We find time not spend working on a project almost as valuable as time spent working on it. Being able to take some distance, and to think things over, helps us improve our work.

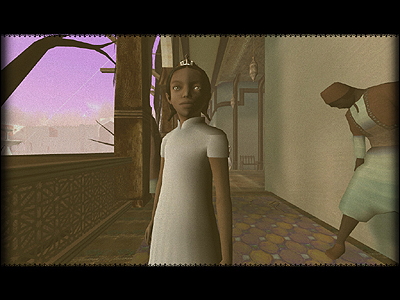

The first project is a prototype for a new game based on our very first design that never made it into production. It’s a dreamy game that takes place in the palace of Sleeping Beauty, 500 years after the princess pricked her finger on a spinning wheel. Eight princes have broken into the palace with the aid of the wicked fairy. But their kisses could not awaken the princess. The forest that once protected the place, is now invading and threatening to destroy everything. As a player, you help a young girl, the “Girl in white” also featured in The Path, but this time younger, find eight objects that were misplaced by the princes, so that, finally, the true prince can come.

The second project is very different from any game we have made before. It’s not based on a story and it doesn’t have characters. It’s an abstract, yet very visceral game inspired by flowers, ancient depictions of the universe, lock mechanisms, cathedral designs and sex. It consists of two parts that we are each working on separately: a male part and a female part. Music will be a big part of the experience. Belgian composer Walter Hus is taking care of this with his band and his giant digitized fairground organ.

These are both very exciting project for us. But the pre-productions alone will take another year. And only after that can we start thinking about production and release. Hopefully people won’t have forgotten about us by then. Maybe we’ll release some smaller things between then and now. Like updates to The Endless Forest. Or the iPad game with Alex Mayhew, mentioned above.

December 2nd, 2010 at 4:59 pm

OOOH! Ross was telling me about The Path – the day we met IRL for the first time, actually. I was telling him that I just didn’t see video games as an interesting, immersive art experience, and he told me about this game. It intrigued me, and I’m so grateful to learn more.

Also, I love their description of Ye Olde Internet. It was totally like that. :)

December 2nd, 2010 at 5:53 pm

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by coilhouse, Teia Pearson, Teia Pearson, s. elizabeth, Maija Plamondon and others. Maija Plamondon said: RT @coilhouse: New blog post: A Telling of the Tale of Tales http://coilhouse.net/2010/12/a-telling-of-the-tale-of-tales/ […]

December 3rd, 2010 at 8:00 pm

“Epic!!!”

December 4th, 2010 at 11:03 am

I love The Path and Tale of Tales! I posted a review of The Path here.

December 4th, 2010 at 12:24 pm

Fatale especially is spectacularly beautiful- I can’t wait for their new projects to be out.

December 9th, 2010 at 12:22 am

The Path & their various other releases have been a welcome change from the standard sea of more mainstream releases. PC gaming has always allowed for far more exploration of game design than its console counterpart simply because the tools have always been available from the get go for ANYONE to make their ideas possible.

Many bigger publishers even releases comprehensive tool sets for this endeavor alone. Epic Games has a LONG history of this with their Unreal Engine. Some beautifully executed highly artistic game mods came out over the course of that engines life (many now largely forgotten or sadly never completed) that showed the benefits of tool sets that were simple to use.

It all began with creating levels & maps really. Many amateur designers added personality, art style, & that magical flow to work that was to be used as Arena’s of digital death. Even today such dated work remains a joy to look at. (sadly we’re in an era where such things are becoming rare. More and more this practice is dying off in favor of publisher sanctioned level & map packs – totally stifling a once integral part of video game creation. Many designers began as amateur map/level makers back in the day.)

Still, you’re seeing a whole new series of titles that ARE deep artistic journeys with merit and depth. The game mechanics may be similar but things like Art Direction, Atmosphere, and more genre bending elements now find their way to the forefront. More tools than ever exist for again, anyone to make a game.

As with the blog post on Machinarium I hope more explore this new indie and small studio explosion of such games. Steam, Xbox Live, Playstation Network, etc. all have categories for these smaller games & some are real gems.

Though one should not forget that above titles like The Path owe a lot to the efforts pushed forward by classics like The Longest Journey (which to this day remains one of the most beautiful games created), Rez (a traditional on rails arcade shooter with one beautiful sense of retro style & recently redone for the HD era), & countless of other Adventure titles which were some of the first to push past the artistic styles and art directions most associate with video games today.

It’s a shame so many only see the big name titles as the picture of Video Games today – it’s like thinking big label artists represent an accurate picture of music being produced.

There are some solid developers pushing video games in directions little explored both in design and artistic styles. Video Games without question are going to be the dominant art form (even though it’s still struggling to be seen as Art) of the next century.

Video games are unique in entertainment in that they can wear so many hats of expression, design, & intent. They also don’t suffer from the limitations of other artforms yet can embrace all they do.

They are also one of the few forms of entertainment that don’t need a story to remain effective yet they can also be built around one from the ground up.

They can be whatever one wants them to be and never passive. They demand interaction and more so these days, personal expression.

@Nadya “I was telling him that I just didn’t see video games as an interesting, immersive art experience, ”

You’re not alone in that opinion. MANY don’t see them as such and video game developers themselves remain divided as to if games qualify as ART but as some have noted – they’ve succeeded well enough without being labeled as such. That may ultimately be their greatest strength. They can be Art to some without having to be Art to all.

December 9th, 2010 at 1:22 pm

Oh my gosh, those teasers for Vanitas almost make me wish I had a smartphone, just so I could play with it. I love that it combines a concept that could be just whimsical, with such solemn presentation.

Thanks for the interview! I’ve been fascinated by Tale of Tale’s creations for a long while now, and it was wonderful to get to hear more about how the pair came together, and to see behind-the-scenes details. Also, I’m going to be thinking about this bit:

“They want everything. They are not making any compromises. Love and death. Destruction and peace. Everything at once. We admire them. When we grow up, we want to be Little Red Ridinghood.”

for quite a while now.

December 10th, 2010 at 8:28 am

Want. WANT! Truly unique and creative at last.