Houdini: Art & Magic – The Wonders Never Cease

Yet another Doomsday has mercifully passed us by. Meanwhile, the horrors taking place around the globe stay their course. Corruption, scandal, and greed continue to rocket to the front pages of our newspapers.

Has there ever been a more dire need for magic?

In the shimmering hills that surround Los Angeles, art, wonder and the hope that only a spectacle can birth are being celebrated. The hard-working ghost of Harry Houdini is traveling the country via Houdini: Art & Magic, a comprehensive retrospective chronicling the life of an immigrant Rabbi’s son turned bonafide American showman. On a recent drive back from Malibu, the first stop on my long-overdue west coast vacation, street markers with stiff black flags trumpeting the arrival of Art & Magic at the Skirball Cultural Center had me jumping out of my passenger’s seat.

I had first seen the exhibit at the Jewish Museum in March before it closed at the end of the month. That same week, Houdini’s last living assistant, Dorothy Young, died in a retirement community in New Jersey at the age of 103, three days before what would’ve marked Houdini’s 137th birthday. The stars were aligning rapidly before me, and I, a sucker for synchronicity, could not churn out the review I wanted in time for the exhibit to end. I sat among pages of obsessive notes describing what I had seen at the museum, from Houdini’s diaries, to photographs of him with his beloved mother, and his performance trunk curling with worn and cracked brown leather. I swooned over the thin, almost romantic curl to his handwriting, lamented his untimely death, and dug up details from the obituaries of Dorothy, a woman who, at the age of 17, had been selected by the magician from a crowd at Coney Island, and kept her stalwart promise never to reveal his secrets.

Alas, the weeks marched on, and life, pitifully, got in the way. I feared my time with Houdini would remain locked in my memory and among the files marked ‘MAGIC’ that crowded my desk. I wasn’t aware that the exhibit would tour, and I had no immediate plans to travel, much less follow it, in hopes of revisiting the man who so fired my own creative appetites and fragile sense of wonder in a world gone batty. When my cousin suggested a turn in our route back to Pasadena through the glamorous streets of Bel-Air, I hadn’t imagined the name to first greet me would be that of Houdini, in bold, white letters, practically a signal flare among the palm trees and jacaranda blossoms.

Magic, however small, lives to surprise us.

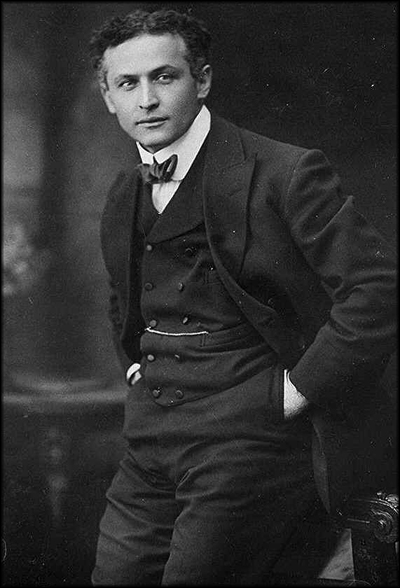

I ventured out to the Skirball that week and relished in my second chance to do right by the man who, after a century, still remains a legendary icon in the psyche of popular American culture, despite his foreign birth and Jewish heritage. Houdini’s wide, glowing eyes emblazoned on a large entranceway banner taunted me with both care and trepidation. Ah, so you’ve returned, he seemed to playfully mock. Just could’t get enough? I entered the darkened galleries and gazed, with fresh eyes, at relics from a time when magic was something to be seen in salon parlors and dime circuses before Houdini and his feats of wonder demanded a stage large enough to enchant the world.

Both exhibits, first in New York and then in Los Angeles, started with a curator’s statement and explanation of how Houdini, a man who made an immigrant’s journey-cum-escape from eastern Europe, became the transformative icon of the American dream across three centuries. Too often modern audiences can take the amazement experienced by a magic show or circus performance for granted, as showmen such as Chris Angel and David Blaine headline extravagant, Vegas-style affairs and Cirque du Soleil and Ringling Brothers make regular returns to most parts of the world. To understand the influence and sheer genius of Houdini is to start at the beginning, which the exhibit explored in depth with respect to his heritage and family.

Born in 1874 in Budapest as Ehrich Weisz, Houdini was the son of Mayer Samuel Weisz and his second wife, Cecilia Steiner. Harboring the hopes of a better life for his family, as many did during that time, Mayer emigrated to America where he found work as a rabbi through a friend for a small congregation in Appleton, Wisconsin, the city Houdini would continually claim as his birthplace. The family followed Mayer, who changed the spelling of his name to Weiss, to America is 1876 with toddler Ehrich in tow. Mayer’s religious views were deemed too old-fashioned by his new community, and he was dismissed from his post, moving his family to Milwaukee when Ehrich was almost eight. Times were hard; from a young age Ehrich sold newspapers and shined shoes to add to the family income. When he wasn’t working, Ehrich pursued athletics and practiced acrobatics, two skills that led him to perform on a trapeze hung from a tree while wearing red socks made by Cecilia. The nine-year old showman billed himself as ‘Ehrich, Prince of the Air,’ and marked the day October 28th, 1883, as his first performance in front of an audience. The transformation of Ehrich Weisz of Budapest to Harry Houdini, the greatest magician in the world, began in the backyards of midwestern America.

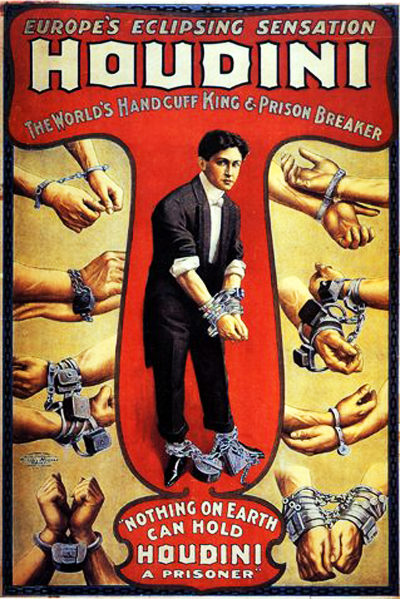

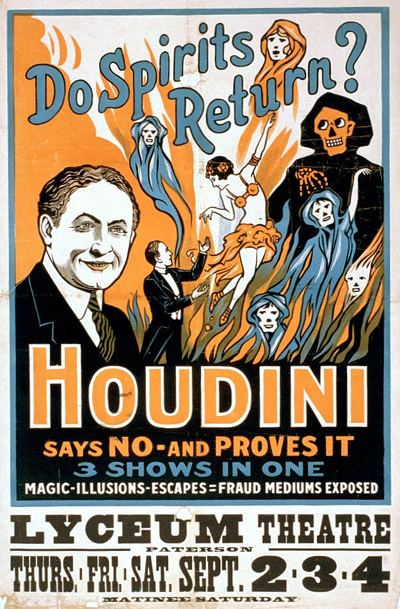

Ehrich’s great escape, a continual theme in his feats of magic to come, began when he hopped a freight car at the age of twelve bound for Kansas City. A year later he reunited with his family in New York City where they were now living, and held a series of odd jobs, from a necktie cutter to a photographer’s assistant, to help the still-struggling household. Around this time Ehrich and his younger brother Theo began to show an interest in magic, with the great French magician, Robert-Houdin, known for his trademark tricks ‘The Marvelous Orange Tree’ and ‘The Ethereal Suspension,’ as Ehrich’s idol. Adding an ‘i’ to the conjuror’s last name and adopting the name ‘Harry,’ Ehrich started performing magic before small groups under his new moniker: Harry Houdini. This would be the name that would grace sideshow posters, theater banners, and street advertisements, later captioned with many subtitles such as “The Mysteriarch,” The King of Cards,” “The World’s Hand Cuff King and Prison Breaker” and “The Justly World-Famous Self-Liberator.”

His professional career began at seventeen doing magic shows for a bevy of venues, including music halls, civic auditoriums, and Coney Island’s amusement park, sometimes performing over twenty shows a day. Harry and Theo worked together for a time as The Houdini Brothers, but Harry’s meeting of the teenaged singer and dancer, Beatrice ‘Bess’ Raymond, would change that. As another performer trying to break into show business, it wasn’t long before Bess soft-shoed her way into Harry’s heart. They married in 1894 and Bess joined the act as Harry’s partner, leaving Theo to pursue a solo career as a magician under the name Hardeen. Devoted to each other, Harry and Bess began a life-long romance on and off the stage, and Harry would credit much of his success to her, as he depended on Bess for every day dealings and personal care. The Houdini’s joined the Welsh Brother’s Circus in 1895, where Harry did magic and Bess sang and danced, together performing the ‘Metamorphosis’ trick that had them switching places in a locked trunk. At the exhibit, a large, lovely photograph from that time of the Houdinis sitting among the strongmen, clowns and gymnasts lay under glass, the grainy sepia tone unable to disguise the happy looks on each performer’s face.

Houdini was never one to be satisfied with the small-scale. He continued to work on magic tricks and develop his speaking voice and showmanship, becoming an expert at handcuffs which would act as his calling card on the road. Once arriving in a new town, Houdini, a natural for excellent publicity, would claim his ability to escape from any police-provided handcuffs, and offer $100 to anyone who could produce handcuffs from which he was unable to escape. Theaters boasted lobby displays of painted posters illustrating Houdini whilst bound and handcuffs affixed to a board, like the free-standing heart shown in the exhibit. The cuffs appeared more like works of art in their own right, with a shine to the thick silver and brass metals, complicated locks and clean design. As Houdini toured, his escapes became more complex, satisfying his hunger to push himself both mentally and physically, and he was soon a headliner on the vaudeville circuit in major American cities. An amusing review of Houdini’s escapes, this one involving a jump in the river while cuffed, came from the wife of the mayor of New York City at the turn of the century. She complained in The New York Times that she didn’t understand what was so special about a man trying to escape from handcuffs; criminals tried to do it every day! Yet Houdini was rarely derailed by the critics. He had larger plans, and took a gamble on bringing his act overseas to the continent that could credit him as one of their own: Europe.

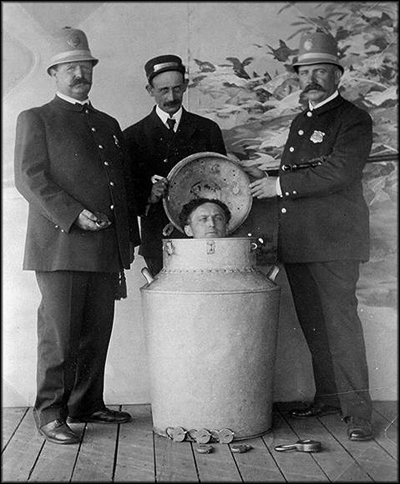

The Houdinis sailed to England in 1900 with no performance prospects a little to survive on after a week. Houdini quickly acquired an engagement at a London theater, and his publicity breakthrough that occurred when he escaped from Scotland Yard after being wrapped around a pillar and handcuffed led the theater to extend his booking. Houdini would perform in London for another six months, and sold-out engagements in Germany were followed by eventual fame all over Europe. The boy from Budapest was a sensation, and wherever he went, Houdini kept his favorite publicity stunt alive and continually broke free from the complicated restraints of the local police, going so far as to jump into rivers and dramatically remain underwater until he emerged, displaying his chains to the cheering crowds. Making about $1,000 a week during this time, Houdini as ‘The Justly World-Famous Self-Liberator’ was born.

Liberation was to be a major motif in Houdini’s feats. Regarded for his raw physicality and grueling, inventive stunts, Houdini’s escape from confinement, be it chains, a milk can, a water torture chamber, or trunk, spoke to audiences who were looking for their own release from the drone of the everyday struggle and the continual search for wealth and success in America, the land of promise to so many like the Weiss family. When Houdini returned to the States in 1905, he was an international celebrity. Not one to rest on his laurels, Houdini used his fame to perform even more astounding stunts, such as the straight jacket escape, the water torture chamber escape, and the milk can escape, these three becoming trademark regulars in his shows. After the canister or chamber was filled with water, with a bound Houdini locked inside, the curtain would close. For what seemed like an agonizing amount of time, Houdini, who usually escaped in a matter of minutes, would keep his audience in suspense before emerging from behind, cheating death for one more show. At the museum, I wanted to wrap my arms around the almost sinister straight-jacket of leather, canvas and brass on display, arms tied behind the mannequin’s back, and crawl into the large metal milk can crowned with padlocks to breathe in what remained of the magician’s struggle.

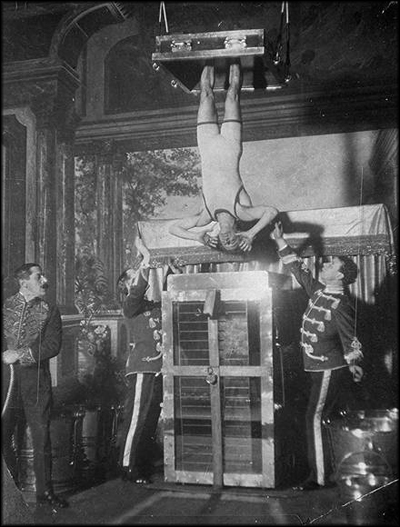

Houdini began to draw even more publicity by hanging upside-down in front of the local newspaper office on the eve of a performance, escaping from a straight jacket whilst suspended over a crowd of thousands. A grainy black and white film showing one of these escapes played during both exhibits, and I found myself making comparisons to super heroes; the symbolic every day man disguised as the strong man entertaining the masses and distracting them from their own despair. The image is unforgettable, no matter if you know the outcome, and the fear that Houdini will plummet to his death on the pavement remains ever-present. He never claimed to have supernatural powers, and took great lengths to stay in peak physical condition, but some of the mystique of Houdini stemmed from his courtship with death. The relief of his escape and the power of a good show did not cloud the fact that, here was an ordinary man, much like those who sat in his audience, placing himself in extraordinary situations, only to claim victory over tyranny, oppression and mortality itself night after night to a paying public hungry for wonder.

Just as it is in the circus, magic is the continual celebration of human possibility. To look at what you know and then question it in the face of awesome, almost unearthly power, be it a human rocketing from a canon, flying from a trapeze, pulling a thread dangling with needles from his throat or escaping for an air tight chamber filled with water, spectacle has served an important human function before there was ever a curtain to be lifted or a big top to erect. Life, for all its beauty, is in fact, a horrifying affair at times, and pure magic exists when one is moved by a terrifying stunt that that suddenly blossoms into one beautiful, perfect image. One of the most important themes in the entire exhibit was recognizing the imagery, or art, that Houdini left behind; a flick of the wrist to display a hand of chosen cards, a lone trunk sitting on the stage, a man suspended over a crowd, or bound and chained with padlocks. Handcuffs were no longer handcuffs when Houdini wore them, but the markings of time like rings on a tree, and even the water in his torture tank seem to ripple with poetry.

For all his ego, as one so hugely famous in his life cannot help but have, Houdini was also concerned with the morality of his practice, recognizing the tricks he employed to turn a dollar and put on a show, but in turn dedicating his showmanship to debunking the link of his tricks to the supernatural. After the death of his mother, Houdini renewed his own early interest in Spiritualism, wanting so badly to believe that there were ways to communicate with the dead, but years of performing had made him privy to the phony methods of so-called Spiritualists. Rejecting higher-paying offers, Houdini went on to lecture throughout the country on fraudulent spiritualists, unmasking many in the cities he visited and demonstrating some of the tricks they employed in his acts. He wrote a best-selling book, A Magician Among the Spirits, and even testified against them before a committee of Congress. Posters advertising Houdini’s debunking of communicating with the dead, photographs of Houdini surrounded by ghostly faces, worn copies of his books on the subject and even a photograph of his beloved Bess in 1936 at a final Houdini séance surrounded by business associates ended the exhibit, the academic side of Houdini showing through from crisp black and white to full color.

Even more than a chronicle of an American icon, an unlikely hero of the working man, and the embodiment of the immigrant’s American dream, the exhibit was, underneath the artifacts of popular culture and memories from countless imitators, a love story. Houdini had three great romances it seemed; one of the soul with his mother, who he adored until her death, one of the heart with Bess, his life-long companion and relentless champion, and the last being of the body with his audience, that adoring public unable to get enough of the man whom nothing on earth could hold. It was to be the this last attraction that proved to be the most fatal.

Unwilling to seek medical care for a broken ankle he suffered during a malfunction in his water torture chamber performance, Houdini allowed a student, on the basis that he could withstand any blow to his body above the waist and below his face, punch him three times in the stomach. Despite the symptoms of chills and sweating that followed, Houdini, ignoring his fever of 102, insisted on completing his performance in Detroit. After the show, Houdini finally agreed to enter the hospital where doctors discovered that he had peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix. Bess, who was in the same hospital for food poisoning, received these words from her husband in his final hours: “Rosabelle, believe.” To the end, Houdini wouldn’t let spiritualists take advantage of the loss of others, and this message was to be Houdini’s proof of communication in the afterlife.

Houdini died on Halloween in 1926, and was buried in the Jewish Machpelah Cemetary in Queens, New York, a pillow containing his mother’s letters placed under his head. For years, Bess tried in vain on the anniversary of her husband’s death to contact him through a séance, and this tradition carried over to fans and followers in recent years. Still, the hardest-working ghost in show business has yet to appear, but through exhibitions such as Houdini: Art & Magic, the curtain can once again be pulled back to show a man as legendary as the feats he created, the time he embodied, and the countless imitators he inspired.

One of the most captivating pieces from the New York exhibit never made it to Los Angeles: Matthew Barney’s “Cremaster 5: The Ehrich Weiss Suite,” a seemingly lighthearted installation of seven Kite Jacobin pigeons bobbing around a locked room, stopping occasionally to defecate on what was supposed to be Houdini’s coffin made from acrylic, and other plastic materials. Mortality is the issue; no matter how legendary you are throughout your life, the elements finally overrule us. Houdini may be long-gone to the earth of Long Island, but his secrets still remain to keep us guessing, just as they did almost one hundred years ago, with his lasting images of freedom he gave to a world never tiring for a hero.

Houdini: Art and Magic is on view at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, California until September 4th, 2011, before it travels on to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art in Madison, Wisconsin where it will open on February 11, 2012.