Breathing New Life into Dead Men’s Patterns: An Interview with Artist Hormazd Narielwalla

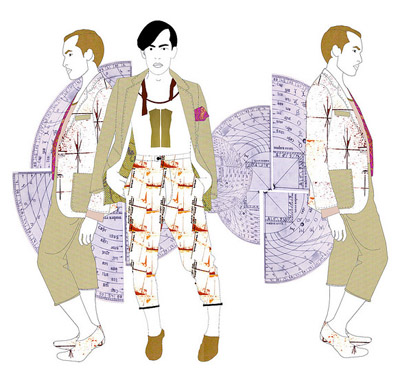

From the “Fairy-God, Fashion Mother” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

Born in India of Persian-Zoroastrian ancestry and now living London, artist Hormazd Narielwalla forages for patterns in historic tailoring archives to use in conjunction with his own photography, sketches and digital compositions, giving their forms new life as whimsical narrative works of art.

You can see some lovely examples of Homi’s unique work in our Issue Six feature devoted to Klaus Nomi. The puppet-like pattern collages are taken from Narielwalla (nickame Homi)’s series A little bit of Klaus…a little bit of Homi. Each Nomi figure contains elements extracted from the vintage bespoke pattern blocks of Savile Row tailors, made for customers now long-deceased. We could not have found a more deeply fitting serenade to the operatic, avant-garde style icon than Narielwalla’s work, with its deft mixture of affection, craft, and thoughtfulness. (Thank you again, Homi.)

In the following interview, Narielwalla tells Coilhouse a bit more about his work and his life. His current show, Fairy-God, Fashion-Mother, which features a series of paper collages inspired by cult curator Diane Pernet, will be viewable at The Modern Pantry in London until January 7th.

From Hormazd Narielwalla’s “A Little Bit of Klaus, a Little Bit of Homi” series.

How did you get started making art, and what eventually drew you to this very specific and personal form of creative expression?

I was pursuing a Masters degree at the University of Westminster, aiming to become a menswear designer specializing in alternate ways of communicating fashion. During one of many research meeting with William Skinner (the Managing Director of Savile Row tailors Dege & Skinner), I acquired a single set of bespoke patterns belonging to a customer, now-deceased.

From the “Dead Man’s Patterns” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

The tailors no longer needed the patterns, as they were made for a shape that no longer exists. With the support of my mentors British designers Shelley Fox and Zowie Broach (from Boudicca), I followed my instinct to divorce the patterns from their original context, viewing them as abstract shapes of the human body instead. That is when and where my first publication, Dead Man’s Patterns, was conceived.

From the “Joe” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

Bespoke patterns are strong dynamic graphic illustrations that have since become my primary source material in making my art. There are whole archives of patterns that are being ignored by fashion, waiting to be explored. I have collaborated with milliners Bernstock & Speirs to create paper military men-illustrations, and now have found shoe patterns. But the Savile Row patterns remain my key component for creative expression.

You’re currently working on your PhD: Patterns as Documents and Drawings. Care to tell us a little bit about that, and the relationship, as you see it, between tailoring, art, and history?

My thesis puts forward several case studies, with which I inspect uniforms and military pattern drafts to derive construction details. Dress historians only work with physical garments, not their patterns. My argument is, you can use both to derive knowledge. I have spent hours in the National Army Museum archive recording fronts, backs, sides, inside-shells, aerial views, and details of the uniforms from the British Raj. I chose this colony because there was an interesting culmination of British and Indian design sensibility, and it also happens that I come from the beautiful Deccan plateaus.

From the “Maharaja Deconstructed” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

My second argument is that tailoring patterns can also be viewed as beautiful shapes in-and-of themselves. They are stylized drawings in their own right. Through my practice I have demonstrated that they have a dynamic, stylized quality that inspires me as an art practitioner. It is important to consider that I am not proposing that the tailoring history is art – I am putting forward a practice where the tailoring history can become a aspect while making art.

From the “Charlie on a Cycle” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

What other fields of study are you consistently drawn to, if any?

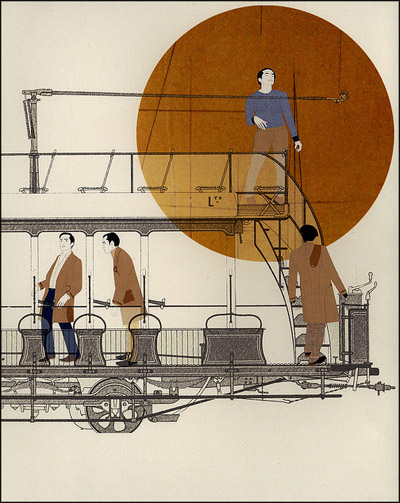

I am interested in Biology, specifically anatomy. I am drawn to skeletons and bones. I am also very interested in architecture, buildings and even industrial machinery and am fascinated with looking at the structural construction – it all comes back to the pattern. The construction of the garment inspires me far more than the garment itself.

Can you tell us a bit about the materials you use, and how and where you collect the patterns?

All of my artworks are collages – some of them are printed digital images combined with actual tailoring patterns. Dimension is a big factor when creating a collage. If the dimensions are small, then I am restricted to smaller pattern pieces – collars, yokes etc. I can use more patterns and bigger pieces if dimension is no problem – like the piece I made for Block Party – a Crafts Council touring exhibit.

From the “Victorian” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

For my current exhibit, Fairy-God, Fashion-Mother, I was commissioned by ATOPOS cvc a Greek visual centre. They have acquired several paper dresses from 1960 and have now a very successful touring exhibition called RRRIPPP Paper Fashion. I was invited to collage both originals and reproductions of the paper dresses with my patterns to create illustrative artworks of the cult fashion curator Diane Pernet.

From the “Fairy-God, Fashion Mother” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

The patterns in my archive come from various sources. My main contributor is the aforementioned Dege & Skinner in Savile Row. I also derive inspiration from the old tailoring books I find in the London College of Fashion and the National Art Library archives. I have used hat patterns in my work – those came from trendy east-end milliners Bernstock & Speirs, and have also worked with delicate tissue home-making patterns.

From the “TramZ” series by Hormazd Narielwalla

What is your background in fashion and tailoring (if any)?

I used to work as a fashion stylist and journalist, contributing to magazines and newspapers like the Times of India back home. Eventually I packed my bags and traveled to sunny Wales to pursue a Bachelors degree in fashion design. Straight after that, I came to London to study under Shelley Fox and Zowie Broach from Boudicca for a Masters in Fashion Enterprise at the University of Westminster.

From the “Maharaja Deconstructed” series by Hormazd Narielwalla

I have no background in tailoring – but I spent the next 2 years working in Dege & Skinner. My responsibilities involved assisting their shirt maker, digitizing the entire archive, and most importantly, putting together the tailoring memoirs of Michael Skinner, the Master Tailor of Dege & Skinner. The book was released this summer; it’s called The Savile Row Cutter. I also spent those years building my practice. I was then awarded the only international scholarship to read on a PhD at London College of Fashion (completion 2013).

From the “Foxy-ED” series by Hormazd Narielwalla

Your work seems very meticulous, yet playful. How do you strike that balance?

I am a Libran — it’s all about the ying and yang! I think life in general needs to have a balance between humor and sadness. You cannot experience one without the other. Some of my projects are “serious” and some are extremely “playful”, like my first ever exhibit A Study on Anansi at Paul Smith’s Mayfair gallery.

From the “Anansi Boys” series by Hormazd Narielwalla.

Reference points are important – if you were to investigate into the Anansi stories, you will find that the character is playful and mischievous. I wanted to bring his character through my work. Whereas the Klaus Nomi figures in my series A little bit of Klaus, a little bit of Homi (Homi being my pet name) have the feel of a puppet and are playful, but deep down his eyes are sad and thoughtful, because that was what I read and experienced while learning about the great performer’s life.

What are you most keen to communicate through your work?

All kinds of stories.

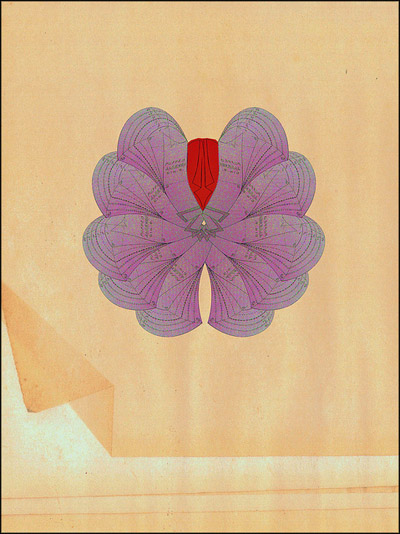

“Vagina” by Hormazd Narielwalla

Who are some of your artistic inspirations? Style inspirations? Life inspirations?

I love the Bauhaus period – can’t wait to incorporate that in a project. Masters like Matisse and Picasso continuously inspire me; I thoroughly enjoy looking at how they communicated their vision. Fashion photographers like Leibovitz, Testino, Mert & Markus are all on the top of my list. What inspires me most are people and their stories. I have a list of people who I would love to invite to sit for me – Grace Jones being on the top of my list, along with Gilbert & George.

Artist Hormazd Narielwalla. Photo by Paul Smith.

Do you have any advice for others who want to express themselves creatively and somewhat non-traditionally, but either don’t know where to start, or don’t or feel like they have the skills necessary to do so?

Be open-minded and allow change to occur naturally. A Danish photographer who was a plumber photographed me recently. His story inspired me – he is a great talent with no academic training in photography. What I’m trying to say is, follow your instinct and do not let anyone stop you in achieving your dreams. Many people were against Dead Man’s Patterns and thought I was foolish to indulge in that project. I was lucky that my parents, along with the many, many porter shifts I took, managed to (barely) fund it. Today my book is proudly archived in the Rare Modern British Collection at the British Library. I am so glad I followed my instinct.

“Anansi In Love” by Hormazd Narielwalla

November 17th, 2011 at 3:54 pm

Fantastic work, wonderful interview. Thanks for this, Mer + Homi!

November 23rd, 2011 at 1:25 pm

Just the title “Dead Men’s Patterns” is amazing! I love how he uses the pattern pieces both to construct and obscure the figures. Wonderful meeting of the technical/formal and playful.