A Tree Filled with Angels: The Visionary Worlds of Jim Woodring and William Blake

Please welcome the second guest post by artist and writer Eden Gallanter! Eden previously brought you an illustrated post on dancing, physics and Mannerstist painting titled The Tango, the Quark, and the Allegory of Love. In this post, Eden discusses the ways in which hallucinations have influenced the work of Jim Woodring and William Blake. Enjoy! – Nadya

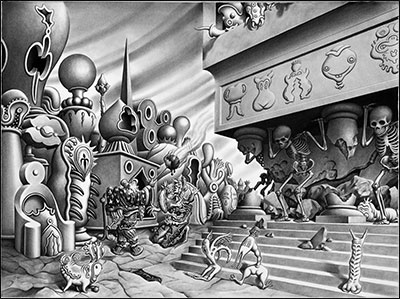

Jim Woodring, “Divornum – or Life After Man”

Although Jim Woodring is a contemporary American cartoonist, fine artist, and writer with a strong cult following, and William Blake was a 19th Century English poet and painter who lived most of his life in poverty and obscurity, these two men shared a common source of artistic inspiration: both experienced visual hallucinations for the majority of their lives.

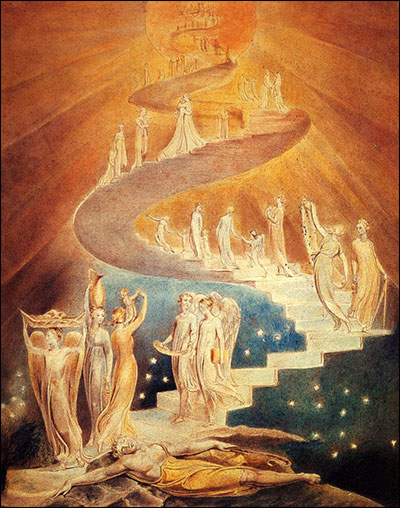

William Blake, Jacob’s Ladder

These visions (or apparitions) are clearly at the heart of both artists’ work, serving as gateways into another world that contains deep human truth and startling strangenesses. One account of Blake’s earliest visions, which remained full of the Christian iconography of 19th century England, describes the four-year-old Blake screaming for his parents upon seeing the face of God at the window. A few years later, he saw a “tree filled with angels,” and was saved from a thrashing by his father for telling a lie by the sympathetic intervention of his mother. Most of Blake’s hallucinations depicted the most beautiful and spiritual of the Christian themes. He also could see and speak to deceased friends, and saw angelic figures and other celestial beings mingled among the everyday ladies and gentlemen of England.

William Blake, Ghost of a Flea

Blake was considered to be a gentle madman by his contemporaries, and although some prominent writers regarded him with interest, his work was largely unrecognized during his lifetime. Upon encouragement by his friends, he painted some of the apparitions he saw, most famously his Ghost of a Flea. Blake’s lovely otherworldly visions, interpreted by him as divine inspiration, gave a confident shape to many socially deviant beliefs and practices. Blake had many ideas about religion that were frankly considered heretical (most notably his The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, which described a unified vision of the cosmos, where both satanic and angelic realms were a vitally important part of a holy and just world). Due to numerous references to the sanctity of romantic love and the necessity of its liberation from oppressive conventions such as duty and possession, Blake has been claimed as one of the forerunners of the Free Love movement in the 19th Century. His poetry is full of rejections of the Christian virtue of chastity, and his writing advocated the removal of bans on homosexuality, prostitution, adultery, and birth control. Blake is said to have lived a happy, quiet life: poor, obscure, and content simply in expressing his visions in his poetry and painting.