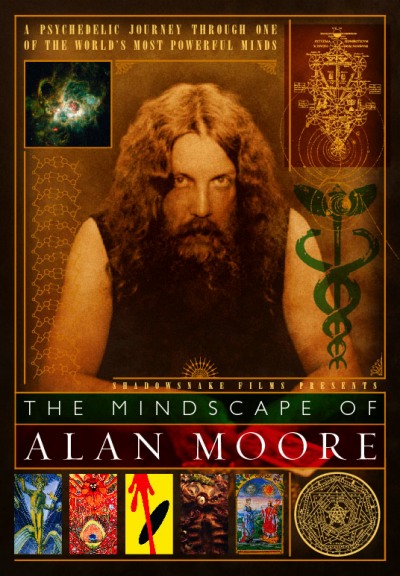

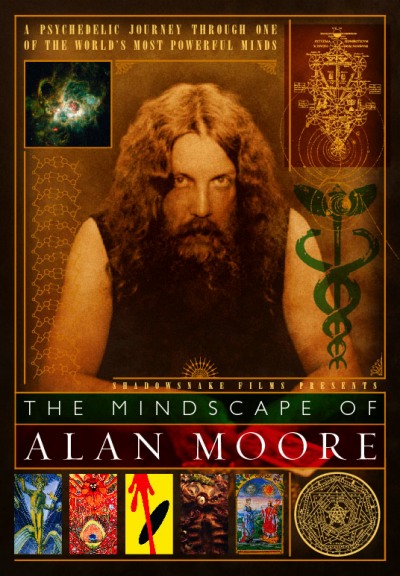

Author/sorceror Alan Moore. Photo by Jose Villarubia, via Swindle Magazine.

A remarkably candid interview with the grand magus of comics writing, Alan Moore, went up today over at the LA Times, discussing, among other things, Moore’s utter contempt for various Hollywood film adaptations of his body of work. Now, I know a lot of folks are really excited to see the new Watchmen movie (based on Moore’s seminal graphic novel, illustrated by Dave Gibbons), and while I’m sorry to piss on the parade, I must admit I’m in complete agreement with Moore that this book in particular (arguably his most influential work to date) is “inherently unfilmable.” I’m glad to see him speaking up. Quoting from the interview:

I find film in its modern form to be quite bullying… It spoon-feeds us, which has the effect of watering down our collective cultural imagination. It is as if we are freshly hatched birds looking up with our mouths open waiting for Hollywood to feed us more regurgitated worms. The Watchmen film sounds like more regurgitated worms. I for one am sick of worms. Can’t we get something else? Perhaps some takeout? Even Chinese worms would be a nice change.

Yes.

I’m fairly convinced that no matter how hard director Zack Snyder tries –and undoubtedly the good man is trying very hard– his adaptation will pale in comparison to the scope, depth and resonance of the original work, just as every other movie based on Moore’s books has failed to measure up. (Sure, V For Vendetta was, well, watchable. Is that really saying much?)

This is not to imply that flicks adapted from other formats are without merit (hell, sometimes they even surpass the original work; Blade Runner, The Handmaid’s Tale, The Excorcist, The Godfather, and The Shining all spring to mind), only that Moore, being a undisputed master of his chosen format, has proved time and time again that one can achieve a sublime kind of storytelling through sequential art that cannot, WILL not be conveyed through in any other medium.

We’ve entered an era ruled by scavengers. We are starving for substance. Obviously, we can’t look to Hollywood schlockbusters to nourish us. Still, the platform of narrative movie making has its own profound and distinctive magic. Here’s hoping that somehow, thanks to the increasing accessibility of equipment and relative price decrease in digital film and editing software, more and more storytellers standing beyond the gates of the sausage factory will be goaded, either by hunger or the pure urgency of inspiration, into making their own moving pictures. Otherwise, we can all just look forward to endless helpings of the same insubstantial, derivative slurry, ad nauseum.

Speaking of substance… I was lucky enough to acquire a copy of The Mindscape of Alan Moore a few months ago. The directorial debut of DeZ Vylenz, Mindscape is the only feature film production on which Moore has collaborated, and given personal permission to use his stories. I can’t begin to tell you what an enjoyable and fascinating documentary it is. It will be officially released on DVD on September 30th.

Alan Moore’s not just one of most important writers in comics; he’s one of the most important writers, period. So really, whether you’re a longtime comics reader or you’ve never delved further than the first issue of Gaiman’s Sandman, the Northhampton Wizard of Words’ body of work cannot be recommended highly enough.