On the Occasion of Walter Benjamin’s 119th Birthday

The treasure-dispensing giant in the green forest or the fairy who grants one wish

– they appear to each of us at least once in a lifetime. But only

Sunday’s children remember the wish they made, and so it is

only a few who recognize its fulfillment in their lives. – Walter Benjamin

Benjamin Birthday Cake! Photoshop by Nadya.

There is a Yiddish expression offered on someone’s birthday which is affectionate and contains a subtle blessing: “Bis hundert und zwanzig.” In other words, people are wished a life that extends to their 120th year. So what should we do if someone dear (if not near) somehow turns 120? What are they wished then and each year thereafter? I offer these questions as a point of entry for considering Walter Benjamin, a writer whose life ended in suicide as he contemplated his chances of eluding the Nazi Gestapo some seventy-three years before this question may have become material for those around him. Today marks the 119th anniversary of Benjamin’s birth – the last time someone could have addressed him with the wish of living to 120.

Walter Benjamin was a literary critic, philosopher, memoirist, and collector during Germany’s ill-fated Weimar Republic. Among his adventures were sojourns from Berlin to Moscow to witness the building of history and to Marseilles to smoke hashish and to Riga to have his love rejected. His last seven years were spent in exile while his works were banned and burned in his native land. Under other conditions, Benjamin’s Francophile desires would have found their easy appeasement in Paris, but the Third Reich cast an increasingly tall shadow and he became, tragically, a prisoner in the country of his dreams. In his forty-eight year life, Benjamin ran with Bertolt Brecht, Rainer Maria Rilke, Asja Lacis, Theodor and Gretel Adorno, Siegfried Kracauer, Ernst Bloch, Hannah Arendt, Georges Bataille, Leo Strauss, Max Brod and Gershom Scholem. And in many ways, Benjamin’s thought is a playful and poetic montage of the ideas of his associates – a “constellation” of Romanticism, Idealism, Marxism, Surrealism, and Jewish mysticism that is more than its unlikely parts: “Satan is a dialectician, and a kind of spurious success…betrays him, just as does the spirit of gravity.”

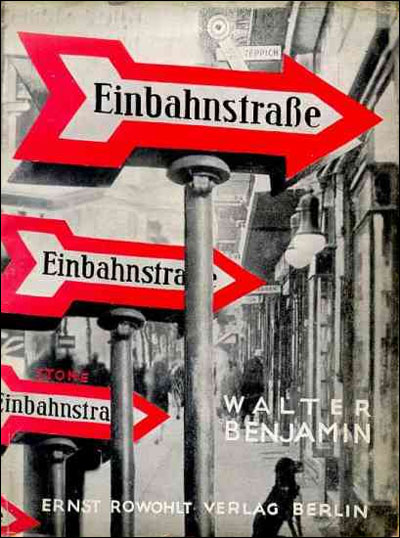

Einbahnstrasse by Sasha Stone (1928)

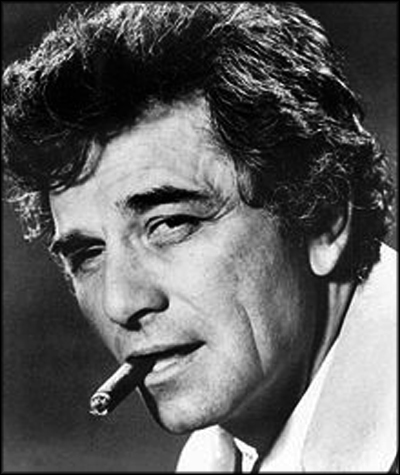

Benjamin brought to this heady mix his fascination, at once childish and insightful, for art and artifacts as relics containing clues to history. The scion of an antiquities dealer, Benjamin discerned an impending revolutionary–cum-spiritual cataclysm by contemplating and indexing paintings, books, and the most banal debris of economic life he could find, regarding them as might wily Detective Columbo if he was prodigiously stoned. As Bloch wrote of Benjamin’s book One Way Street, “when the current cabaret passes through a surrealist philosophy, what emerges into the light of day from the debris of meanings…is a kaleidoscope of a different sort.” The spooky thing is that Benjamin’s apocalyptic vision of lawmaking described in 1921 as “bloody power for its own sake” came to pass in many ways a little more than a decade later.

Walter Benjamin lived in a milieu of such vastly assimilated German-Jewish life that he had little formal understanding of Jewish culture, Yiddish, Hebrew, or even the Jewish religion. He did, however, harbor an abiding interest in Jewish mysticism and mused furtively over those bits of religion and culture he encountered. And he certainly seemed to have found spiritual sanction for his already-existing fetishization of objects in the Kabbalist’s meditations on words, names, and numbers. According to this mystical orientation, influenced by neo-Platonism, reality has multiple dimensions – like a faceted diamond – only a few of which are directly accessible to us. We may approach them only indirectly, as they appear to us as abstract notions like numbers, letters, names, and sentiments. In such times as Benjamin playfully, and perhaps also earnestly, speculated on the mystical significance of language and numbers, he may have come to consider 119 alongside its constitutive outside, the number 120, the last year we can legitimately hope for someone else. If so, it is entirely likely that Benjamin, a thinker who invited the mystical, would have been intrigued by the delimiting function of 120 and may have further speculated on 121 as a possible portal to other dimensions. Operating, then, as a detective, Benjamin may have investigated the year 120 as a future crime scene – a time-place where this phrase will be eternally transcended. Looking outward, 119 years of life may have been considered the furthermost edge of his generation, a remote vantage from which to contemplate the eternity of space, like a balcony atop “Saturn’s ring.” Upon returning from such reveries, Benjamin would hopefully have finally mentioned that the actual root of this folk expression comes from the biblical datum that Moses lived to be 120. This, then, could have been followed by an analogy that is possibly both specious and interesting, like noting that Moses and Benjamin never completed their exodus from brutality.

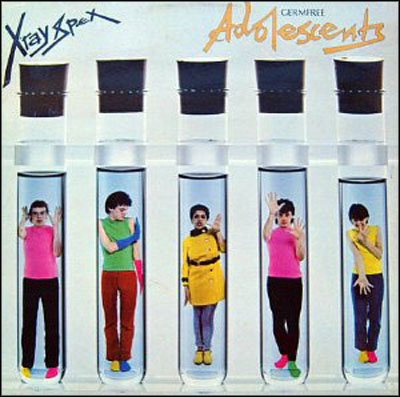

The wish that one live beyond the culturally sanctioned, and quite generous, lifespan of 120 is redolent of the posthumous reception of Benjamin’s work throughout the humanities. The fervent interest in his work throughout the humanities since the 1980s is so unlikely as to seem almost a form of Messianic fulfillment on an individual scale. After all, his life was unfulfilled in most respects. He was a failed academic, a divorcee whose affair was an awkward mess, a minor radio personality whose voice was never recorded, and a writer whose masterworks were unfinished or forever lost in history. Years later, his work even achieved “fame” on its own terms when, in 1969, his most significant essay was mistranslated as “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” by Harry Zohn. For Benjamin, a work has achieved “fame” when it its translation transmits information not contained in the original. Two generations of scholars and art critics referenced his most significant essay through a misleading title, when now, as if language shifted its tectonic plates under our feet, the essay is emphatically translated as “Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” In the digital age, articles like this one are re-posted with attention to errata, such as mistaking today for his 121st anniversary, whereas it is only his 119th. If only Zohn had used WordPress his translation would have been unfinished and arguably better for it. Perhaps as the author of that essay – however titled – Benjamin would have come to consider fame in the age of American Idol in terms of having a finger puppet refrigerator magnet in one’s visgage. “All that is holy is profaned,” sayeth Marx. What does familiarity breed? So much for the “aura” of the author, eh?

The wish that one live beyond the culturally sanctioned, and quite generous, lifespan of 120 is redolent of the posthumous reception of Benjamin’s work throughout the humanities. The fervent interest in his work throughout the humanities since the 1980s is so unlikely as to seem almost a form of Messianic fulfillment on an individual scale. After all, his life was unfulfilled in most respects. He was a failed academic, a divorcee whose affair was an awkward mess, a minor radio personality whose voice was never recorded, and a writer whose masterworks were unfinished or forever lost in history. Years later, his work even achieved “fame” on its own terms when, in 1969, his most significant essay was mistranslated as “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” by Harry Zohn. For Benjamin, a work has achieved “fame” when it its translation transmits information not contained in the original. Two generations of scholars and art critics referenced his most significant essay through a misleading title, when now, as if language shifted its tectonic plates under our feet, the essay is emphatically translated as “Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” In the digital age, articles like this one are re-posted with attention to errata, such as mistaking today for his 121st anniversary, whereas it is only his 119th. If only Zohn had used WordPress his translation would have been unfinished and arguably better for it. Perhaps as the author of that essay – however titled – Benjamin would have come to consider fame in the age of American Idol in terms of having a finger puppet refrigerator magnet in one’s visgage. “All that is holy is profaned,” sayeth Marx. What does familiarity breed? So much for the “aura” of the author, eh?

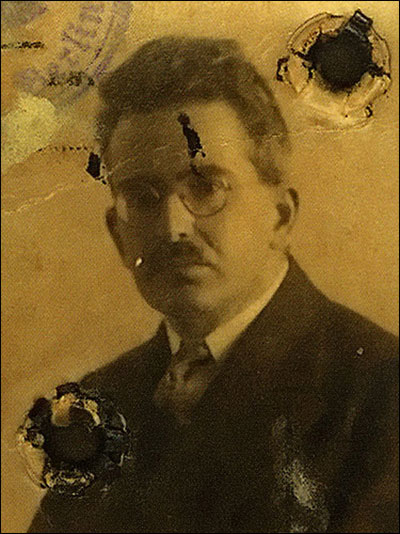

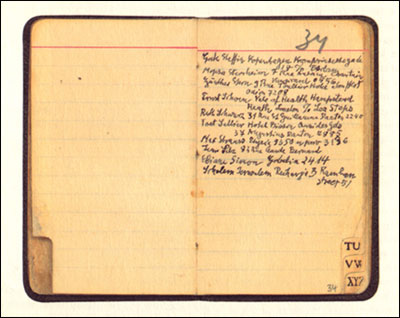

In his essay on “The Metaphysics of Youth” Benjamin contemplates one’s diary as a temporal domain, an inner life expressed in writing which begins in medias res, with life already in motion, and which can never be concluded by an author whose death occludes continued authorship. The project is never finished and the life, as written in the diary, exists in its own sort of time, like the life the mind, an eternal moment delimited by birth and death, and unable to experience either. Benjamin’s life is thus suspended within the pages of his books, essays, memoirs, and personal effects – as in his Paris address book shown below. Something of his life may sometimes seem to flash in our minds as we read him, just as Benjamin once suggested that art and artifacts can communicate something of their creation in flashes. In this sense, Benjamin’s work has escaped the bounds of the moment in which it was written, although it has yet to allow its readers to tear the fabric of time and usher in the Messianic moment of utter destructiveness in which history is fulfilled and completed.

Of course, I cannot literally wish Walter Benjamin 120 years of existence because I have no known way of communicating it to him. I can, however, wish it for him in spirit, and I do. Whether this wish, now communicated in language, effectively gives him happiness, is beyond the scope of this essay to determine, but my wish that it do so has some affinity with Benjamin’s own work. In his essay, “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man,” Benjamin posits language as constitutive of thought and life as we know it – not merely a conduit for them – as, in his example, a divine speech act once set the universe in motion with illumination: “Let there be light.” Likewise, Benjamin may have noted that the wish that someone live to 120 implies a blessing, as in the Yiddish expression: “From your mouth to God’s ear.” As this is the last time I may properly wish Walter a 120th year, I am ever-more concerned that it take the form of a blessing where numbers and sentiments are tangible – on the other side of language.

This essay is dedicated to Lionel Ziprin, z”l.