All Tomorrows: Sovereign Bleak

I always thought danger along the frontier was something that was a lot of fun; an exciting adventure, like in the three-D shows.” A wan smile touched her face for a moment. “Only it’s not, is it? It’s not the same at all, because when it’s real you can’t go home after the show is over.”

“No,” he said. “No, you can’t.”

Story goes like this: there’s an emergency ship en route to a plague-ridden planet, carrying essential medicine. The pilot finds a stowaway; a young girl, Marilyn, who just wants to see her brother.

The pilot now has a problem: he has enough fuel to get himself to the planet, but no one else. Interstellar law is clear: all stowaways are jettisoned immediately.

But space captains are heroic sorts. Whatever harsh decisions the author puts in their background to prove their grit, this is still a story. This time will be different. Marilyn is the perfect, plucky sidekick-in-training; surely the pilot can figure out some way to save both her and the planet’s populace.

No. There is no solution. She says her goodbyes and is ejected, with “a slight waver to the ship as the air gushed from the lock, a vibration to the wall as though something had bumped the outer door in passing, then there was nothing and the ship was dropping true and steady again.”

The above is from Tom Godwin’s The Cold Equations. When it came out in Astonishing Science Fiction in August, 1954, it shocked the hell out of the magazine’s readership, used to the last-minute triumph of human ingenuity.

Godwin’s classic was only the beginning. The ensuing decades would see American sci-fi delve into realms unthinkable to its forebears. Desperate to shake off the genre “urinal,” as Kurt Vonnegut so succinctly termed it, writers first ditched one of the key assumptions: that the hero will always save the day. Maturity, in this view, meant uncomfortable truths. Often, it meant unhappy endings, not just for the protagonists, but frequently the entire world.

This is a scattershot story of how the bleak tomorrow came to reign, and how it changed our visions of the future.

“Granted that not all stories need to be morally edifying, nevertheless I would demand of science fiction writers as much exercise of moral sense as I would other writers… In my opinion, such abstractions as honor, loyalty, fortitude, self-sacrifice, bravery, honesty, and integrity will be as important in the far reaches of the Galaxy as they are in Iowa or Korea.”

— Robert Heinlein, Ray Guns and Rocket Ships, 1952

Editor John Campbell would not have it. Isaac Asimov might be his protege, and one of Astounding‘s leading lights, but that didn’t matter, not this time. No story of humanity ground under the heel of alien overlords would get by on his watch. The young writer adapted his pitch, suggesting to Campbell that the story could focus on humanity’s resistance, drawing a nice parallel with the world war then raging.

Campbell wasn’t buying it. His “penchant for human superiority over extraterrestrials,” as Asimov would later describe it in his memoirs, was a hard limit. Humans might face horrors, like the shapeshifting marauders in Campbell’s own classic “Who Goes There?” (the basis for The Thing) but they would eventually triumph. Heinlein could foresee fundamentalist dictatorship (“If This Goes On…”), but it would be overthrown. Asimov could write the occasional apocalypse, like “Nightfall,” but the horror had to happen to aliens on a distant planet. People were more badass than that, and however many innovative ideas erupted from Campbell’s shop, the triumph of human reason and its technological spawn remained gospel.

By 1954 things were changing, and Campbell was attempting to drag Astounding and science fiction (the two were inseparable in his mind) into a more respectable place. Most of Campbell’s moves towards serious critical regard involved clever reason puzzles, the occasional social issue and (in Asimov’s words again), writing “scientists that talked like scientists.” While this made for some influential technical prognostication, its world of rocket ships and computers remained in many ways mentally conventional as ever.

Ok, so even Campbell had some cynicism about space travel.

However, Campbell’s changes did leave science fiction a little more open to a darker perspective than before. Hence he picked Tom Godwin for his next trick. Already an established part of Astounding, Godwin had less than a year earlier crafted the unusually nightmarish The Gulf Between, with human soldiers turned into uncaring robots, and so seemed particularly suited to take up his editor’s gruesome kernel of a story. The result was “The Cold Equations,” an unusual experiment for both Campbell and Godwin. Campbell actually requested the downer ending and, according to a 2006 roundup of memories of the famed editor, sent it back to the ingenious Godwin three times, because the writer kept finding ways to save Marilyn from a cold death.

For all that it stunned sci-fi readers, Godwin’s tale remained the exception for years, a dire prophecy crouching on the shelf. Tales of far futures remained tied to a very specific image of human (and American) technological progress: often challenged — but never defeated. In 1956, in one of the many polemics he wrote in Astounding, Campbell declared that “Science-fiction is written by technically-minded people, about technically-minded people, for the satisfaction of technically-minded people.”

Ray Bradbury, however, was no damned technician.

The first concussion cut the rocket up the side with a giant can opener. The men were thrown into space like a dozen wriggling silverfish. They were scattered into a dark sea; and the ship, in a million pieces, went on, a meteor swarm seeking a lost sun.

“Barkley, Barkley, where are you?”

The sound of voices calling like lost children on a cold night.

“Woode, Woode!”

“Captain!”

“Hollis, Hollis, this is Stone.”

“Stone, this is Hollis, where are you?”

“I don’t know. How can I? Which way is up? I’m falling. Good god, I’m falling.”

They fell. They fell as pebbles fall down wells. They were scattered as jackstones are scattered from a giant throw. And now instead of men were only voices—all kinds of voices, disembodied and impassioned, in varying degrees of terror and resignation.

—Ray Bradbury, “Kaleidoscope”

While the Astounding nucleus fancied themselves the center of science fiction, Bradbury had put out a work easily as prophetic as Godwin’s, and earlier.

During the ’50s Bradbury and similar writers such as Jack Vance and C.L. Moore, along with The Twilight Zone, drew from a very different current than the starry-eyed technicians over at Astounding. This tradition dated back to the more psychological pulp writers and Stephen Vincent Benet’s heady apocalypses. In their narratives, technology was less the point than a trapping to primal dramas and fears, a reason why Bradbury and Rod Serling often crossed so easily into fantasy and horror.

The Illustrated Man was a collection of stories, mostly published in obscure, short-lived magazines from earlier in Bradbury’s career, framed around the unifying theme that all these visions are inked into the flesh of the eponymous man by a mysterious woman from tomorrow.

They’re justly considered classics and reading through them is a window into the strangest of dreams. “Kaleidoscope” begins with the concept that its spacefarers are absolutely doomed. Terrifying, inhuman children use technology to finally solve the hindrance of their parents in “The Veldt.” Interminable Venusian downpours drive explorers to madness in “The Long Rain” and the devastating story “The Rocket Man” brings home, through a child’s eyes, the costs of taking on the void that lies just beyond our atmosphere. “The Last Night of the World” is, as one might guess, exactly what it says on the package; a devastating apocalypse without a bomb or zombie in sight.

By the force of logic, Godwin and Campbell had, in their own ways, begun to puncture the old myths (even Campbell’s own). Space, they realized, was bigger and nastier than we wanted to comprehend. There was no way around many of the more awful implications of fragile ape-things wading into the vastest unknown imaginable.

Bradbury and cohorts arrived at a similar place by a poet’s route, foreseeing that the future unfolding before humanity would be as viscerally terrifying as wondrous.

To be sure, Bradbury wasn’t the only harbinger. Fritz Leiber, for example, had toiled in much the same tradition, if with a little more love from the sci-fi gatekeepers.

But, at least back in the early ’50s, when people thought sci-fi, they didn’t think Bradbury. They thought Asimov, Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke, who famously said that if humans were to have any future “for all but a vanishingly brief instant near the dawn of history, the word ‘ship’ will mean—’spaceship.'” We would get to the stars, dammit, and the future still promised a more rational, more capable humanity than previous generations.

Times change, however, and the new generation of sci-fi authors had grown up in a time of war, discord and nuclear scare. Their visions would be quite different from the unstoppable arc of progress that Campbell had foreseen.

Limp, the body of Gorrister hung from the pink palette; unsupportedhanging high above us in the computer chamber; and it did not shiver in the chill, oily breeze that blew eternally through the main cavern. The body hung head down, attached to the underside of the palette by the sole of its right foot.

It had been drained of blood through a precise incision made from ear to ear under the lantern jaw.

There was no blood on the reflective surface of the metal floor.When Gorrister joined our group and looked up at himself, it was already too late for us to realize that, once again, AM had duped us, had had its fun; it had been a diversion on the part of the machine.

Three of us had vomited, turning away from one another in a reflex as ancient as the nausea that had produced it.Gorrister went white. It was almost as though he had seen a voodoo icon, and was afraid of the future. “Oh, God,” he mumbled, and walked away. The three of us followed him after a time, and found him sitting with his back to one of the smaller chittering banks, his head in his hands. Ellen knelt down beside him and stroked his hair. He didn’t move, but his voice came out of his covered face quite

clearly. “Why doesn’t it just do us in and get it over with? Christ, I don’t know how much longer I can go on like this.”It was our one hundred and ninth year in the computer.

-Harlan Ellison, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream

By the time the above story appeared in the now-defunct science fiction magazine If, in early 1967, Bradbury and Godwin’s occasional nightmares had infected the medium as a whole.

Much of the new wave of sci-fi took the fears of yesteryear and went into pitch-black hole territory. Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth” appeared the same year as the legendary Dangerous Visions, which he also edited. Between them, they helped define the tone of a new era of storytelling.

Out of Dangerous Vision‘s legion of classics, the most extolled punctured and inverted the reigning myths of the genre. Samuel Delany’s Nebula-award-winning “Aye, and Gomorrah…” played the astronaut fetish to a particularly vicious twist. Joanna Russ’ famous When it Changed (from the sequel Again, Dangerous Visions) saw long-lost adventurers from Earth as chauvinistic brutes (and won a Nebula). Kurt Vonnegut, the crossover literary star of the bleak era, summed up his own attitude bluntly in the title of his own story, nestled right next to Russ’: “The Big Space Fuck.”

Think, for a second, at the futures they envisioned and then look at “I Have No Mouth…” Ellison’s capstone. This is a story that sees an apocalypse so pitch-black it almost makes The Illustrated Man look tame (no small feat). In this future, not only is humanity nearly wiped out, the remaining five people are nothing but playthings for the pinnacle of human technological achievement: a hateful (and how!) supercomputer whose sole goal is to mutate and torture them. Victory, if they can gain it, consists only of finding a way to finally die. Yeah, you might need a drink after reading this one.

How far the genre had come in its ferocious embrace of human frailty was quickly indicated by the starkly different reception Ellison’s dark talesmiths got, compared to their predecessors.

Ellison, expressing his usual outlook.

Bradbury, for example, had always been on thorny terms with the sci-fi establishment, not least because of his abrasive personality and Luddite rants. Ellison was now embraced, even though he shared many of Bradbury’s same characteristics on both a literary and a personal level. (The intro to Ellison’s 1978 collection Strange Wine remains one of the most concentrated doses of misanthropy set to paper). Bradbury, whatever visions he conjured, and however crotchety he might be, retained a boy’s belief in the redemptive power of dreams, as well as their horror. Ellison’s breed of evolved nightmares were leaner, deadlier, with less sentiment, and not one drop of pity.

In 1954, “The Cold Equations” was regarded as a terrifying, if brilliant, oddity. In 1970, it was voted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. The writing on the wall could not have been more clear.

“What sort of criticism is it to say that a writer is pessimistic? One can name any number of admirable writers who indeed were pessimistic and whose writing one cherishes. It’s mindless to offer that as a criticism. Usually all it means is that I am stating a moral position that is uncongenial to the person reading the story. It means that I have a view of existence which raises serious questions that they’re not prepared to discuss; such as the fact that man is mortal, or that love dies. I think the very fact that my imagination goes a greater distance than they’re prepared to travel suggests that the limited view of life is on their part rather than on mine.”

-Thomas Disch, throwing one back at the sci-fi readership.

However, if the nail needed to be pounded into old sci-fi’s coffin any deeper, Thomas Disch’s Fun With Your New Head also hit American shores in 1970. Disch first became known for the post-apocalyptic survival tale The Genocides, which manages the difficult feat of making most after-the-end and alien invasion fare look positively cheery by comparison.

Fun‘s odyssey, and Disch’s, were in many ways emblematic, for while he was an American author, the collection of short stories, many published in the more daring magazines, had first been compiled two years earlier in the U.K. as Under Compulsion. The role of British sci-fi in shaping the American New Wave and the Deviant Age it created is a massive topic, and one worthy of way more attention than I can spare here. Suffice to say that, with its own triumphal future dreams crushed in the trenches of World War I, British sci-fi already tended to be of a bleaker, far more complex nature and less confined to genre. It made sense that Disch’s tales found fertile ground there first.

Just to top off the historical synchronicity, Disch was famously accused, by Philip K. Dick, in finest batshit conspiracy mode, of cooperating with a Nazi plot to spread rumors of syphilis outbreaks. Dick, like a dire comet, exercised a huge amount of pull on sci-fi’s mutation in this era, but was so enthralled by his own unique trajectory that his writing reflects less of the archetypal bleak universe that Ellison and others were crafting.

But what kind of a writer was Disch? Russ, analyzing in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction almost a decade later, offered the best description: “Thomas Disch is a sinister writer,” and yes, the italics are all hers, “I mean by this that his work… is an ominous attack on the morals and good customs of Middle America.”

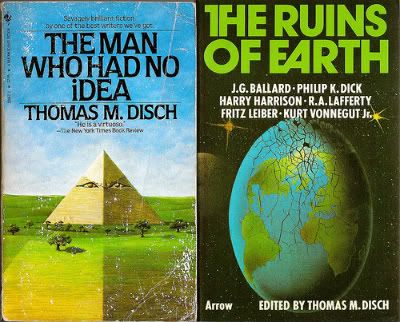

The covers of two archetypally Dischean works.

Disch personifies much of the genius of the trope-inversion prodded along by Bradbury and Godwin’s experiments, and Fun reflects that as well. Despite the clunky titles (by the time of its publication becoming a trend with more intellectual sci-fi fare), there’s some brilliant stuff here. “Now is Forever” is one of the most under-appreciated masterpieces of the era, prophesying the contradictions in the replicator-world of transhumanist cyberpunk long before that school of thought even existed. Disch was canny enough to foresee that a world in which everything is abundant is also a world where everyone is disposable. “Moondust, the Smell of Hay, and Dialectical Materialism” is a lost spaceman lament that remains haunting in its simple tragedy. Disch even pays homage to the Bradbury/Twilight Zone roots of the bleak style with some tight horror tales (“The Roaches” and “Descending”).

Yet while Disch was certainly no covert Neo-Nazi, he was perhaps one of the only sci-fi authors to put Ellison to shame in the number of axes he had to grind. In one way, Fun can come off as a litany of these. Read it and you will find a practical encyclopedia of Disch’s dislikes (straight culture, government, capitalism, communism, New Yorkers, non-New Yorkers). He did not merely dislike these things, but beat them with word after word until they were a messy pulp.

After I first found a yellowed copy of Fun, a game developed among some similarly sci-fi inclined friends: a free drink for anyone who could read the entire table of contents out loud before bursting into laughter. No one’s made it past “Flight Useless, Inexorable the Pursuit.” Most of Disch’s work — though Fun probably contains some of the best — was a good deal better than the titles, and some was worse. Stories like “1-A” and “Casablanca” just come off as ham-handed hatefests against extremely stereotyped versions of the military and arrogant American tourists, to name just two of his countless gripes.

Disch went a step further than his predecessors, systematically stripping away even the alternate futures some of the Deviant Age’s scribes dashed to in an attempt to find an alternative to dystopia. Amongst all his ranting and hacking, he found time to deliver blows to dreams of enlightened psychic aliens (“Nada”) and human-built utopias (“Thesis on Social Forms and Social Controls in the U.S.A.”).

The best we could look forward to, in Disch’s universes, was the final liberation that comes with utter collapse:

At midnight Jessy Holm was going to die, but at the moment she was deliriously happy. She was the sort of person that lives entirely in the present.

Now, as every light in the old Exchange Bank was doused (except for the blue spot on the drummer), she joined with the dancing crowd in a communal sigh of delight and dug her silvered fingernails into Jude’s bare arm.

“Do you love me?” she whispered.

“Crazy!” Jude replied.

How much?”

“Kid, I’ll die for you.” It was true.

-Thomas Disch, “Now is Forever”

Any artistic backlash, no matter how brilliant, contain within it the seeds of its end, and this bleaker tomorrow was no exception. In addition to Disch’s talents (and Fun‘s publication, representing an archetypal tale in the rise of bleak sci-fi) these stories also showed much of what eventually caused the trend to wind down to exhaustion. It’s not as if harsh endings were unheard of before, or happy tomorrows missing from the Deviant Age’s works (utopian stories sprang up like flies on shit from 1965-85, to the point that Delany and many others actively inverted it) but the effort to subvert and grow past its founding myths flipped the ratios: what had been the exception became the rule.

Nor did it sit well with everyone. In 1982, another famed Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction reviewer, Algis Budrys (who had praised many of the above writers), mourned that the boom of the ’70s was over and “retrenchment is everywhere, and peripheral matters are being cast overboard by a publishing establishment tending more and more plainly toward the surefire action drama of limited ambition.” He also observed, more than once, that the quest for critical approval behind all those tortured titles and characters could stifle just as much as the whims of the marketplace. In a way, perhaps, the new breed, like Campbell’s old guard, continued to write for a small clique, with academics replacing technicians.

In 1995, while developing a computer game based on “I Have No Mouth…” Ellison was asked by game designer David Sears why AM was so set on torturing his five victims. He had to admit that he had no idea.

In 1967, sci-fi needed a designated anthology to finally be dangerous, edgy and bleak. As I write this, the SHINE anthology (which you should buy), has hit the stores. It is designated specifically for optimistic sci-fi.

The cover of the SHINE anthology, by Vincent Chong. In many ways a deliberate rebuke to the futures crafted by the bleak school.

Go into a bookstore today, and in some ways the children of both the Golden and Deviant Ages are present. You will see legions of military sci-fi series — often descendants of the older school, with more blood and less wonder — and plenty of apocalypses as well. Yet the heart of both schools seems missing. There is stunning sci-fi being made today (often in television and graphic novels too) but much of the animating visions that shaped both the Golden and Deviant Ages seem gone, with little to replace them in the popular mind.

It’s worth noting for a moment that most of the above stories were short, and as the short story has drastically fallen out of fashion, the sort of “wham!” impact much of the best sci-fi thrived on became harder and harder to market.

The initial Golden Age of sci-fi made such an impression that it demanded a reaction, and for all its brilliance, its myths were full of so many arrogant holes that they were far more rickety than they seemed.

There was, perhaps, a difference of attitude in the generations too, for we often forget that sci-fi is as much an alternative culture as a school of writing. Campbell’s generation and their works were drastically shaped by the fact that they were, mostly, men of science and technology (“written by technically minded people… for the satisfaction of technically minded people”). The Deviant Age storytellers, though weened on their predecessors, proved, well, deviant. They were psychologists and lit nerds, queers and feminists, political radicals and outcasts of an entirely different sort from their genre ancestors. Less concerned with machines than possibilities, they often also possessed the analytical skills to dissect their forebears, and comment on what was evolving. It is not coincidental that true literary criticism on the nature of sci-fi emerged in this era.

For all that the Golden Age writers were open-minded or even willing to leap full into the bizarre about some topics (Dianetics crawled from this ferment, remember) the technically innovative visions they created tended to take current social values for granted. Men would still be men, women women and the epitome of pioneering American capitalist technocracy would endure forever, but IN SPACE. Some — Heinlein and, more brutishly, Campbell’s final acolyte Jerry Pournelle among them — were more explicit about this traditionalism, but even the more liberal Asimov and Clarke believed in a tomorrow that still represented a form of mid-century rationalism.

That was what the Deviant Age’s bleaker architects were rebelling against, and I think it explains some of the gusto with which they dismantled the previous myths.

So it was that while Bradbury may have distrusted technology, and often seen space as a place for horror, he could still exult at the moon landing. A decade and a half later Ursula LeGuin (one of the more optimistic crew to come out of the newer generation) would dismiss space travel in a Mother Jones interview as “a bunch of crap flying around the world, just garbage in the sky.”

Sci-fi has always been an outcast, but a surprisingly influential one. More mainstream cultures may commonly mock it, but it’s still not uncommon to turn to its sages to comprehend what the newest development means for the world.

Yes, it might be argued, all these visions were simply responding to the crises and feelings of their time. Perhaps. Certainly massive upheavals made ripe soil for the bursting of myths.

But we often forget that the building of new tales still requires acts of individual genius. Contemplating the terror of space does not alone produce “The Cold Equations.” Everyone can imagine an apocalypse. It took Harlan Ellison to give us “I Have No Mouth.”

The stories they crafted, as bit by bit these authors hauled up new icons over the sacrificial pyre of the old astronaut dreams, did change things. By 1979 the big screen still saw humanity venturing into space — only to face terrifying aliens on behalf of soulless corporations. A direct line can be traced through the visionaries above to Alien, Blade Runner and the cyberpunk and zombie horde visions that dance around our pop culture mind today. Go back and read Watchmen right after leafing through Dangerous Visions and you’ll see the common roots. Just as their predecessors’ rocket-ship visions eventually made their way into popular consciousness, so our age still bears the infection of the apocalyptic and the grotesquely wondrous tomorrows bequeathed to us by the writers mentioned above, among many others. It is telling that commentators now speak of Dick and J.G. Ballard as architects of our age. The suburbs, to use Ballard’s words, “dream of violence,” and the space program remains a slowly dying afterthought.

The popular vision of tomorrow turned away from a triumph over the stars, to cyberpunk and apocalyptic freeways. The spaceships stalled and we began to see the future not in where we might go, but in what might pulse buried under our flesh or come to destroy us some black day. The stars were not meant for humanity, and earth might not be either.

Yet, in the process, science fiction and the worlds it considered — the worlds we could consider — grew immeasurably. Bradbury, Disch, Ellison and others who I have mentioned in passing here, whatever their faults, set out to radically mature the genre they so loved. They went to excess, sometimes laughably, but they inarguably succeeded.

Every culture that makes its vision heard infects us, sometimes in ways so vitally small we don’t even realize it. We do live in the Golden Age’s world of rockets and computer conversations. But we also live in Sovereign Bleak’s world of the consequences of our own ingenuity fallen full-bore upon our minds and culture. What we’re typing on those computers has far more to do with Ellison and Disch, Russ and Delany than it does John Campbell. What had gone to the stars was brought crashing spectacularly down to Earth, for a while, and perhaps we’re better for it. But it’s time to start asking where the story goes from here.

Show’s over. What now?

April 12th, 2010 at 5:45 pm

Spacegoddamned good to have you back.

April 12th, 2010 at 7:46 pm

Wow David. God damn. You need a smoke after writing that? I know I do now.

April 12th, 2010 at 11:03 pm

I’ll second that Wow, incredible essay on Sci-fi. I hadn’t quite realised what was missing from most of the stuff I’ve been reading but I think that it’s all cleared up a bit for me now. I need to find more “wonder” in my Sci-fi.

On a second much shallower note, I think I’ll be crushing for quite a while on that spirit of the future that Vincent Chong created^^

April 12th, 2010 at 11:54 pm

Good essay man, good essay indeed. I always felt that the reason I liked Philip K. Dick’s work was that it feels so plausible. Unlike the work of say Heinlein I can relate to the characters in Phil Dick’s short stories. And like I said, the world he describes feels so real. Very plausible. (Okay, not the part where women walk around half naked)

April 13th, 2010 at 3:14 am

Very impressive work, sir.

As a would-be-writer of speculative fiction, I have to say, very thought provoking.

I grew up reading Golden Age stuff, and then got steeped in the pop culture of the Dystopian Second Wave, and now find myself caught somewhere in between, convinced that we humans are going to make a total cock-up of it all, but that we’ll live to ride out our mistakes, and maybe eventually come out the other side. Sometimes I think we’ll come out all right, and sometimes I confident what comes out the other end of the meat grinder will be as similar to us as sausages are to pigs.

April 13th, 2010 at 3:59 am

Great post -haven’t read much sci-fi lately, but this made me want to go back & check out some old favorites, try another book or two. I also remember how Grant Morrison revitalized the moribund Justice League of America comic-book several years ago, by reinjecting some ‘sense of wonder’ in it too, yet it seems that most of today’s audience is not so keen on “big idea” writing. Oh well-

April 13th, 2010 at 5:14 am

[…] Coilhouse Magazine, in an article called ‘All Tomorrows Sovereign Bleak‘, David Forbes mentions SHINE as an antidote against the predominant bleakness of the […]

April 13th, 2010 at 7:32 am

Brilliant essay. Absolutely brilliant. Love the critical dissection.

April 13th, 2010 at 11:26 am

This was a delight to read — and I very much enjoyed the link to “The Gulf Between,” which I hadn’t read before.

Sharing this with my daughter, who is something of a Bradbury fan as well . . . although I’ve just found out that she hasn’t read “The Illustrated Man,” which I’ll have to remedy :D

April 14th, 2010 at 6:23 am

Damnit, David. Brilliant piece, you suave bastard. Well done!

April 15th, 2010 at 6:56 am

[…] the meantime, please enjoy the ever-encyclopedic David Forbes’ mind-blowing essay, “Sovereign Bleak” (via Coilhouse) on sci-fi landmarks and the philosophical trends that shaped […]

April 15th, 2010 at 9:52 am

Just as a note, and I wish I remembered the name, but a decade or so ago, I read a reply to _The Cold Equations_; same scenario, but the story ends with the pilot cutting his legs off and jettisoning them, enough to equal the weight of the little girl. He doesn’t need them to land the ship, after all.

April 16th, 2010 at 3:44 pm

I’ve been devouring this in small doses since it’s been posted. No doubt like all the previous entries I’ll revisit it again & again. All Mr. Forbes entries are like that…but this…this is special. Not only is it a grand feast of ideas and information but there is just so much in it to further explore and fall into.

Brilliant post, good Sir.

April 30th, 2010 at 8:19 pm

Wonderful essay. However, I would be remiss in my fanboy duties if I did not mention the relevance of the writing of one Mister Peter Watts in this context, who’s website prominently features the quotation “Whenever I find my will to live becoming too strong, I read Peter Watts.”

May 19th, 2010 at 4:00 am

A sterling essay, one of the best I have read on sci fi in a long time. You have outdone yourself here.

May 19th, 2010 at 4:01 am

Oh and re the Peter Watts suggestion, yes he fits stylistically but not date wise. I reccomend his wonderfully acerbic essay ‘Hierarchy of Contempt’ and his best novel, ‘Blindsight’