The Evolution of Fashion as a Signifier

Coilhouse guest blogger Numidas Prasarn previously brought you an article on Fe Maidens, the all-girl high school robotics team from the Bronx. In her second guest post on Coilhouse, Numi talks about fashion as a signifier of status and identity, and how the emergence of the middle class, along with globalization, have changed the pace at which fashion trends are manufactured, adopted and discarded. Numi demonstrates this phenomenon by walking us through the evolution of the men’s three-piece suit. An academic #longread sure to delight fashion/history/socioeconomics geeks! If you enjoyed “Starch Makes the Gentlemen” and “Teddy Boys,” this article provides some excellent context. – Nadya

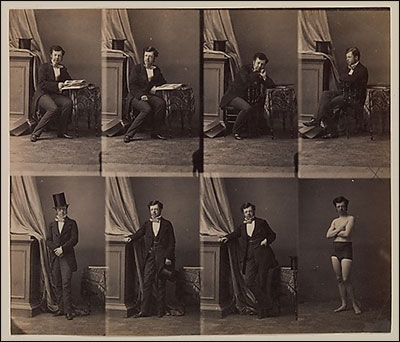

Prince Lobkowitz, 1858

Fashion as signifier is a concept familiar to many that identify as part of an alternative tribe or culture. How we express ourselves, how we identify with those around us, what style says about us and our culture – fashion is often examined through this scope. But how do we explain the origin of how trends in fashion move, how do we create these signifiers to begin with? There are many ways to approach this, one angle is the idea that fashion and socioeconomics are inseparable, that style and social politics are more intertwined than initially imagined and more specifically that globalization and the growth and reign of the middle class changed the game of fashion.

That is an awfully heavy statement to lay in one sentence.

Allow me to back up for a moment. There is a list of reasons designed to answer “Why do humans wear clothing.” They are Protection, Modesty, Identification, Adornment, and Status. Right now I am going to focus on Identification and Status, particularly in relation to using fashion as a means of establishing class division. German sociologist Georg Simmel puts it in terms of Imitation, Union and Exclusion. He writes that:

“Fashion is the imitation of a given example and satisfies the demand for social adaptation […] At the same time it satisfies in no less degree the need of differentiation, the tendency towards dissimilarity, the desire for change and contrast, on the one hand by a constant change of contents, which gives to the fashion of to-day an individual stamp as opposed to that of yesterday and of tomorrow, on the other hand because fashions differ for different classes – the fashions of the upper stratum of society are never identical with those of the lower; in fact, they they are abandoned by the former as soon as the latter prepares to appropriate them.” [1]

Up until the 20th century, the largest shifts in style, silhouette and beauty have been directly linked with the changes of the ruling class. A trend established by the aristocracy and shared amongst themselves, it becomes a marker establishing what class the wearer belongs to. It is therefore a means of creating Status and allowing Identification, and on a deeper level creating an environment of Exclusion/Inclusion.

The game changes completely with the entrance of the middle class. After the Industrial Revolution but before WWI, you see an interesting shift start to happen where importance in the aristocracy turns instead to the working class. The idea of the self-made man and the nouveau riche become the new aristocracy and the middle class undergoes a growth spurt. Still young in its identity, it upholds a lot of the ideals it was taught to value and is a prime example of Simmel’s concept of Imitation. Post WWI, the notion of an aristocratic ruling class dies and so ideals change. From here on out, changes in trends happen faster and in a more cyclical manner. It isn’t that we ran out of ideas or new needs, we merely established that upward mobility was possible and therefore trends became more accessible. To use Simmel’s terms again, Imitation and Inclusion became possible on a wider scale which meant Exclusion had to happen at a faster rate.

Let’s demonstrate by examining the evolution of the male wardrobe, specifically the reign of the 3-piece suit.