The angel bent his gaze severe

Upon the Tempter, eye to eye,

Then joyful soared … to disappear

Into the boundless, shining sky.

The Demon watched the heating wings

Fading triumphantly from sight

And cursed his dreams of better things,

Doomed to defeat, venting his spite

And arrogance in that great curse

Alone in all the universe,

Abandoned, without love or hope

– from The Demon by Mikhail Lermontov

Long ago I promised to return to one of my favorite subjects: madness. Currently I’m fueled by days of non-stop drawing, surviving on coffee and deviled eggs alone. In other words – the time is right. We’re looking at the madness of prolific Russian painter Mikhail Vrubel. When we left off some months ago, Vrubel was living in Moscow with his beloved wife and son. His massive works in oil, based mostly on Russian folklore, had earned the prolific painter a fair degree of fame and success. The illustrations to Lermontov’s poem The Demon that launched Vrubel’s career receded into the past. Mikhail was working in the theater alongside his wife, painting and designing costumes for her operas, immortalizing the beautiful singer as each of her fairy tale characters. His life was the epitome of creative and family bliss. His new paintings were glowing, as well, due in part to the subject matter and in part to iridescent bronze powder Vrubel mixed into the paint.

The Seated Demon

Nevertheless, Vrubel was compelled to return to the enormous portrait of the Demon. Slowly he began reworking the brooding features, even after the work had been exhibited. Painting thick layers upon layers in an attempt to convey the demon’s pure despair drove Mikhail further away from life, deeper inside himself and his work. The poem’s nihilistic themes seem to have struck the very heart of the artist. Despite his success and marriage, was there a sense of ultimate loneliness permeating Vrubel’s reality? Did the poem reveal a world as he secretly saw it, confirming his latent misery? Was he never genuinely happy, resenting his family life and fame? Perhaps, instead, there was an overwhelming fear of losing what he treasured most, triggered by the loss of his siblings as a child and fermenting inside ever since. Or was it The Demon‘s contempt for the Church that struck a chord? Vrubel’s obsession grew, taking over his body of work and eventually producing a dozen paintings and sculptures dedicated to The Demon. So much paint has been compulsively applied and re-applied that many details of these paintings are nearly indistinguishable, but the Demon’s large, restless eyes and dark features stand out, thoroughly spellbinding. Burning through the viewer, this is Vrubel’s best work, stunning, unhinging and unforgettable.

Details of Demon In Flight and Demon, Downcast

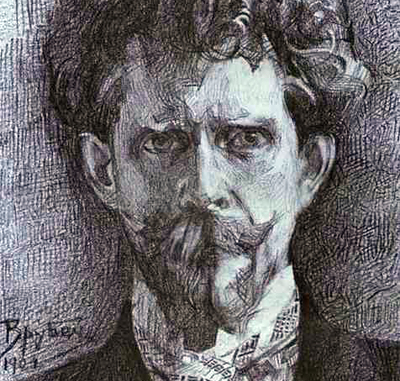

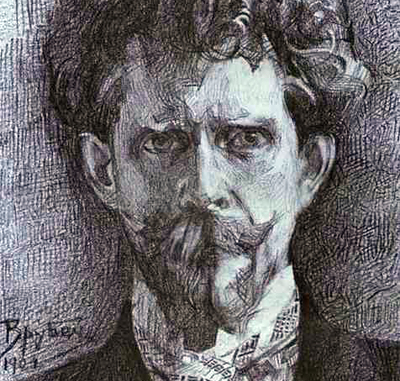

in 1902 Vrubel was briefly hospitalized due to failing emotional and physical health. The Demon had had left him powerless against reality and he was beginning to crumble. Home from the hospital, his health was improving, but recovery was short-lived. Just a year later Savva, Mikhail’s beloved son, died. With grief aggravating an already fragile mind, Vrubel continued his slow decline. He also continued to work, finally abandoning the demon that caused so much agony and returning to portraits and fantasy. I’m particularly fond of this drawing – the concerned visage of the artist’s psychiatrist.

Portrait of Psychiatrist Fiodor Usoltsev

Several years passed until the first signs of every artist’s worst nightmare showed themselves: Vrubel was losing his sight. This was the final blow to his health and spirit. Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel, one of the greatest Russian painters, met his end in the clutches of pneumonia at the age of 54. He purposely made himself sick by standing in cold spring air earlier that year, the Demon, surely, at his side. If you visit Moscow’s Tretyakov gallery, be certain to complete the tour – at end, after halls upon halls of classic Russian art, in Vrubel’s room he waits.