Arturo Herrera Revisits “Les Noces”

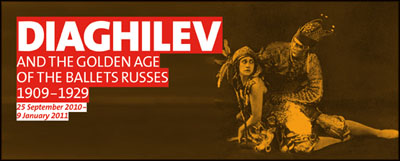

A still from the 1923 Ballet Russes’ production of Les Noces.

Les Noces, known as Svadebka in Russian, was a production ten years in the making. Originally commissioning the score from Igor Stravinsky in 1913, Sergei Diaghilev, creator and leader of the Ballets Russes, intended the ballet to be choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky. The task was later handed to his capable and innovative sister, Bronislava, who was inspired by Cubism, Constructivists, and the relationship between body and machine as exemplified in the emerging Soviet Russia. More concerned with the dynamic quality of movement rather than the traditional posturing and composition of ballet, Nijinska’s choreography was novel and intensely physical.

With its premiere in 1923, Les Noces acted as a sacred drama that created a liturgy out of a wedding while exploring brutal peasant values through a modernist lens. The dancers, in their somber, simple costumes designed by Natalia Goncharova, were to resemble Byzantine saints leaving little room for expression or romance as they stabbed and spliced the air and stage with their rigid hands and feet. The result was one of the most enduring and influential ballets of the 20th century, still performed today.

Conductor Leonard Bernstein spoke of Stravinsky’s opening “cruel chord, made crueler with the lack of preparation,” and the unsettling score stays with you long after the final note has been sung. Influenced by the ‘folk orchestras’ of peasant weddings, Stravinsky employed only four pianos and soloist singers for his musical score, a far cry from the sweeping ensembles found in his compositions The Firebird, Petroushka and Le sacre du printemps. Now, New Yorkers and visitors to the famously noisy metropolis can get lost in the soundscape of Stravinsky as appropriated by the artist, Arturo Herrera.

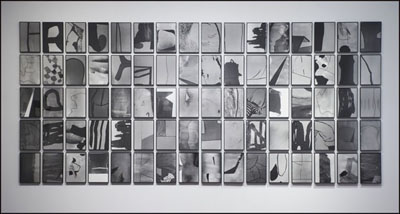

On view at the Americas Society until April 30th, Herrera’s Les Noces (The Wedding) is an abstract homage to the classic ballet in the form of jumpy film projections, collage and sculpture. Take the time to visit the modest exhibit if only to experience the rattling pianos and piercing operatic vocals of the Stravinsky recording, haunting as any eulogy, juxtaposed against Herrera’s film of a world as bleak as Nijinska’s peasant girls all too aware of their fates.

The gallery at the Americas Society is located at 680 Park Avenue, NYC and is open Wednesday through Saturday, 12-6 p.m.

Click here for more information on the exhibit. For further reading on Les Noces, visit Ballet UK.