Where Have You Gone, Lando Calrissian?

EDITOR’S NOTE: Here’s another insightfully inciting essay from Jeffrey Wengrofsky, who is currently co-starring as Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York City in Speakeasy Dollhouse, a real life, vice-filled murder mystery set in a former speakeasy on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Directed by Cynthia von Buhler, the production’s cast has also included Edgar Oliver, Kate Black, Edgar Stephen SNAFU, Katrina Galore, Amanda Palmer, Neil Gaiman, Katelan Foisy, Dana McDonald, Ali Luminescent, Heather Bunch, Porcelain Dalya, Russell Farhang, Amber Baldet, (Silent) James Lake, Rachel Boyadjis, Justin and Travis Moore, Syrie Moskowitz, Maria Rusolo, and Josh Weinstein, to name a few. Everyone we know in NYC’s been going gaga for this production, so please check it out and report back!

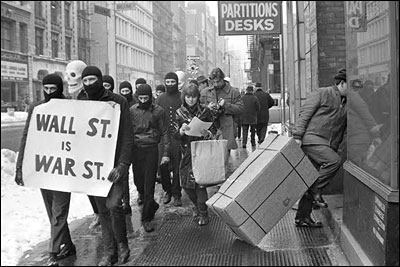

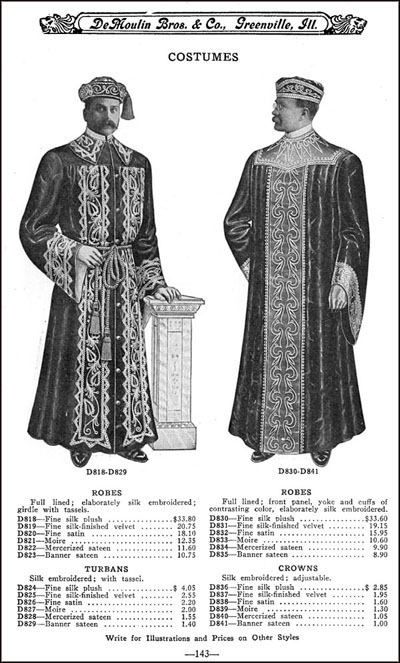

New York as Cloud City. Photo by Heather Allen.

“Suddenly everything became clear!

This was the…Atlantis of Plato…There it was before my eyes,

with undeniable evidence of its catastrophic end!” – Jules Verne1

After DJing at the Coilhouse Black & White & Red All Over Ball last August, I came down hard and fast. As a resident of lower Manhattan, I winced at the oncoming anniversary of 9-11 and braced for the immediate impact of Hurricane Irene. Media experts speculated that my neighborhood, barely three feet above sea level, would soon be under the swelling East River, and I imagined New York City’s primordial industrial artery oozing green across my lobby like that scene in The Shining when the blood comes out of the elevator. After a trip to the local store for batteries, canned goods, and bottled water, I got on my elevator with a veteran of Burning Man who shared information about high tides, planetary formations, and the Mayan calendar, bringing together science, new age pontificating, and classic Lower East Side pessimism to pronounce absolute DOOM on the city, the United States, Western civilization, and the world as we know it.

In the least it seemed certain that my building, only a block from the river, would join New Orleans, Indonesia, and Bangladesh as places where people waited atop roofs for relocation by helicopter. My dear friend and fellow Coilhouse contributor Angel Polacheck, herself an evacuee from New Orleans, appealed to her personal experience of relocation and invited me to travel with her to Pittsburgh, but after weighing my fears and imminent responsibilities (my fall semester teaching responsibilities beckoned from the coming week), I resolved to go down with the city. Having been born only a few blocks from where I now live, I imagined myself reclaimed by this land, neck deep in slimy muck with the likes of Jimmy Hoffa and the wrecks of old sailing ships on the gooey bottom of the East River. Hatches were battened in defiance. My computer was fastened to the National Weather Service for constant updates. Rain fell hard against my windows. Waters swirled and rose. As I drew a bath for future use, I stared at the water – my nemesis. What could be more innocent than water and who was I to defy it? Conscienceless, unconscious nature seemed poised to dish out death with the blank remorselessness of the bear in Grizzly Man. I compiled plaintive dispatches from the new Atlantis and contemplated the worst.

Damn the clichés: will rising tides sink all ships?

As it turned out, Irene did not tuck New York into its riverbed with a long “goodnight.” Instead, she spat her guts out all over New England and upstate New York, flooding several towns and small cities. New York City incurred minimal damage, but the hours of anxiously awaiting my fate left an impression on me. Shortly thereafter, my building, like much of the Northeast, undulated during an earthquake possibly attributable to natural gas fracking in Virginia. In the past ten years, a sense of looming cataclysm—whether from ecological disaster, nuclear conflagration, terrorism, martial law, biological contagion, or economic implosion—has settled on people I know, forming a sad, silent backdrop to our lives. We are resigned to our coming undoing, but we do not yet know what form it will take; so we grin and grind and grunt toward a collective future that none of us will have consciously chosen.

While one of the conversion points of the left and right of the political spectrum may come at the oft-professed fashionable desire to see New York City destroyed, such an event would drown the entire global economy, which would be more than a merely “inconvenient truth.” Besides, rising sea levels will inundate every coastal city and small town in the world and the millions of soggy, displaced persons washing up on every door will make a mess not easily absorbed by any society or economy. And if, somehow, you are still savoring some schadenfreude, then contemplating the water shortages, heatwaves, tornadoes, earthquakes, or forest fires soon to be visiting the hinterland should stir the embers of empathy in your Grinchly heart.

To paraphrase Joe Strummer: New York is sinking and we all live by the East River.

Where have you gone, Lando Calrissian?

- Jules Verne, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Trans. A. Bonner. (Bantam Books, 1962). p. 256. ↩